This is the first of three articles I wrote for the Hiroshima Signpost magazine about my overland journey from Hiroshima to Berlin in September 1991. In this article, I leave Japan by ferry from Osaka and arrive in Shanghai three days later.

Departure

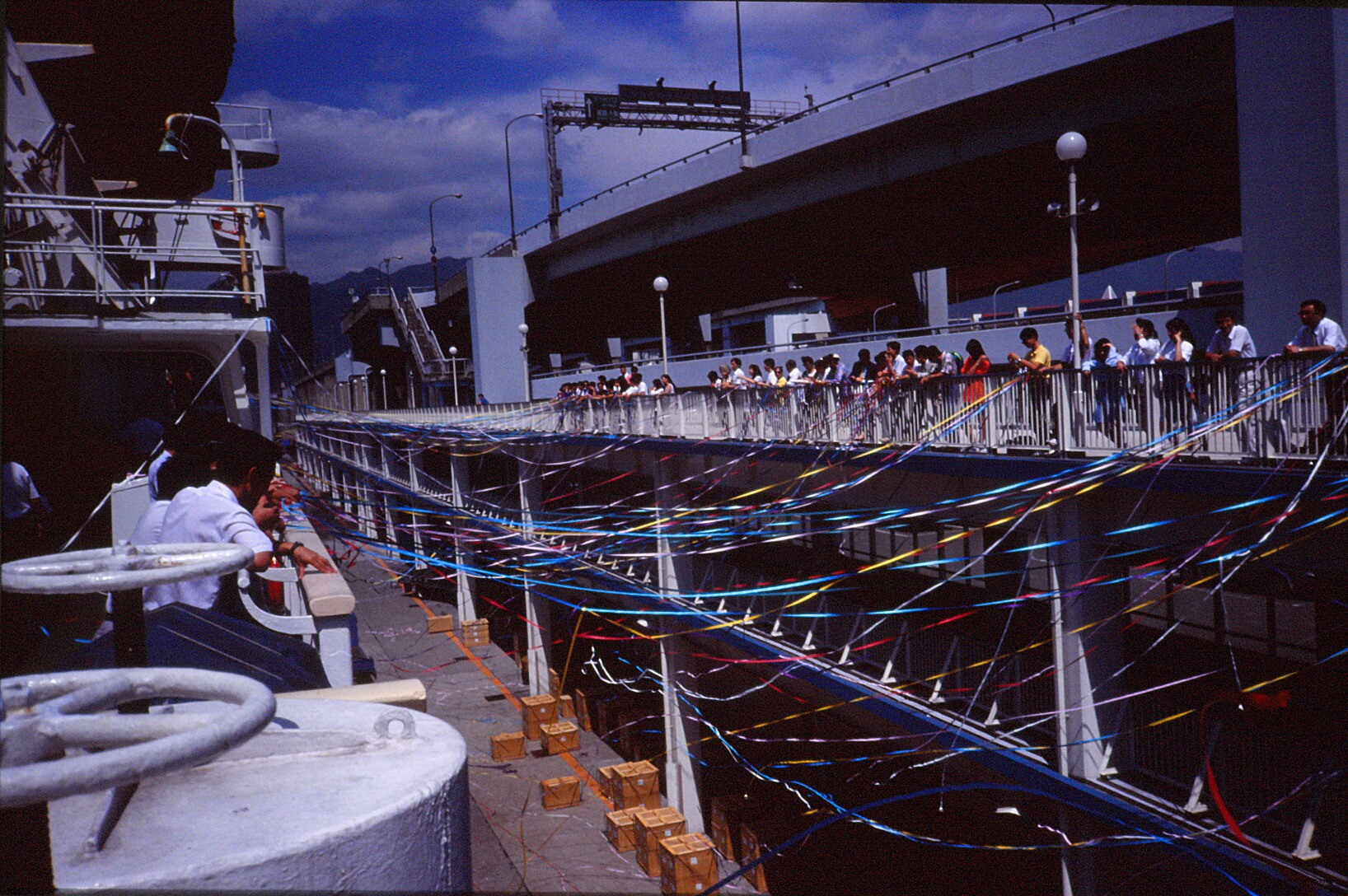

All that bound us to Japan in the early afternoon of the tenth of September 1991 was an array of streamers stretching across from the railings of the viewing platform to the starboard rail of the ferry. The mooring ropes were released and as they slithered home the ribbons stretched taut and snapped, waving ineffectually on the breeze. Passengers and well-wishers waved and shouted inaudible parting messages to each other. Cameras clicked, video cameras whirred. One fellow prolonged the pain of departure by paying out streamers tied end-to-end as if he were flying a kite, until even he had nothing more to grasp.

Then the deck hands came along and bundled the ribbons into gaudy bird nests and hurled them into the sea.

The Shanghai-bound ferry leaves Osaka Bay and proceeds along the southern coast of Shikoku, the western and southern coasts of Kyushu before heading out into the East China Sea. Apart from a couple of hours when the ship rolled about on the second night, the East China Sea proved to be as smooth as Japan’s Inland Sea, and free of typhoons.

Nor did the two days on board seem particularly tedious. I was adrift and secure between the past, which I had come to love, and the future, which I did not know. Between waking and sleeping the day was divided by three leisurely meals.

For canteen slop the food was reasonable and various. Japanese, Chinese and Western dishes were approximated and slipped down well enough when accompanied by a bottle or so of Kirin or Shanghai beer.

There then remained but a few hours for reading, rummy, staring into space, and grinning inanely at fellow passengers. Should these pursuits wax sere and tedious, light entertainment could be sought in the “supermarket” – a teasingly ironical appellation going some way to counter the commonly held prejudice that the Chinese (for we were, by the way, on a Chinese ferry) lack a sense of humour.

The illusion of not really having left Japan could be maintained by loitering near the beer and pot-noodle machines, by wallowing in the rather murky waters of the on-board sento, and by going up on deck to contemplate the “very Japanese” coastline before it finally gave way to open sea.

I went up onto deck at 7:30 on the third morning. The sea was calm again after the turbulence of the previous night, but as far as the horizon in every direction it had turned to slurry, and no land was yet in sight. Above, the sky had come closer and loured upon us as only a grey sky can.

Gradually a grey and unprepossessing coastline sheepishly presented itself; the south-eastern edge of the flatlands which stretch about five hundred miles west to Tschengtschau on the Yellow River and around the Schautung Ridge in an uncompleted O to Beijing, six hundred and fifty miles to the north. The Yangtse flows along the southern rim of the flatlands, and it was the effluence of this river which had so coloured the sea. But not this alone, I am sure, for Shanghai, which is situated on the southern shore of the estuary mouth seemed, as we drew near, to consist entirely of oil refineries, iron and steel works, chemical plants, textile factories, coal yards and loading bays with cranes slung menacingly over them.

Arrival

As we approached the ferry terminal we passed naval vessels freshly painted as grey as the scenery. Tugs lugged barges of coal two abreast across our bow in insouciant disregard of our foghorn. Every vessel seemed perilously overloaded, with turbid waves rippling over the gunwales and soaking the cargo. Every vessel appeared to have been recently raised from the bed of the estuary and pressed back into service. The air was full of soot.

The colour palette of the suburbs of Shanghai echoes that of the neighbouring sea. The streets are the colour of the water, the buildings the colour of the naval vessels, though in a rather more parlous state of repair. The vehicles produce sooty clouds of exhaust and appear never to have been less than thirty years old. The sweet lap-lapping of the sea is replaced by the guttural sonority of expectorating men.

It began to rain. A group of Chinese was huddled by the entrance to the port.

“Excuse me,” said one of them. “Are there any more Japanese on the ferry?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Do you want to change some money?”

“No, I already have.”

My wallet was fat with Foreign Exchange Certificates. I was getting wet.

“But you can’t buy anything in shops with FEC,” he protested.

Rates of Exchange

He seemed to have a point. He and his friends seemed pleasant enough; students of Japanese eager to practice on the Japanese tourists who had by now disappeared in taxis and tourist coaches to safe havens. Being something of an expert in the language myself and unfamiliar with the local lingo, yet desirous to mix with the natives, I condescended to humour my companions by exchanging a hundred FEC at an unfavourable rate. Gill, my erstwhile colleague who accompanied me as far as Beijing, followed suit. There followed a swift unfolding of wallets from pockets and banknotes from wallets. Crisp mint tourist currency fled before the face of the grubbier, well-fingered genuine stuff and everything folded back into place again. We had arrived in China

.

Our new-found friends proposed that we have lunch together and “talk about Japan” in exchange for which they would find us a cheap hotel. A marvellous proposition; but first I wanted to buy an umbrella.

The process is as follows. You wander into a convenient department store and wave an arm or two in the direction of the brollies. The assistant, blessed with the charm of industrial soap, responds with the celerity of an action replay, and within the hour you find yourself confronted with a bewildering choice of black, non-collapsible, and black, collapsible. Being a pragmatist, I selected the latter and, anticipating a speedy closure, I brandished a wad of the grubby stuff. It didn’t wash. I was handed a slip of municipal toilet roll and directed to another counter, where I once again brandished my wad, from which a disagreeably large chunk was extracted in exchange for another slip of the municipal roll, which, for some reason, required both a signature and a counter signature. I was then directed back to the first assistant and, eagerly awaiting a third slip of paper, was rather taken aback to be given a black, collapsible, umbrella.

Our friends led us across muddy streets teeming with donkey carts, taxis, and cyclists – many of whom pulled trailers loaded high and wide with merchandise. Our friends led us beneath stretches of bamboo scaffolding – employed to prop up dilapidated facades as much as to anticipate their renewal – until at last we stepped down into a dingy, meanly furnished, fly-infested room.

A vast quantity of dishes were called for, fish and vegetable, along with copious supplies of Shanghai beer. Passers-by stared, passed by, then reappeared to stare some more. The master occupied himself by swatting flies. He was a dab hand at it, though rather unsporting, only going for the ones that had settled.

Two or three hours later I was escorted across the road and down a back alley to the gentlemen’s room. A couple of plastic dustbins stood against the wall. The procedure is quite simple (toilet slippers are not provided). You piss into the already brimming bin and think of Archimedes. “It is the Chinese way,” explained one of the students who had accompanied me, a statement with an oddly familiar and comforting ring to it.

A few more beers, another session of money-changing and, finally, the arrival of the bill, which, for some unaccountable reason came to rest with an ingratiating nonchalance at my elbow. Not being one to indulge in petty snivelling haggles over filthy lucre I brushed aside the inarticulate protestations of the former colleague and with a pertinacious affirmation of that munificence for which I am, though I confess it myself, somewhat reputed, and handed the lubricious landlord the dough. It was, after all, I have since reasoned, no more extravagant on the purse than a healthy night on the tiles down the Nagarekawa in Hiroshima.

Hotels, Breakfast and Hell

Strolling through the centre of Shanghai of an evening one is afforded the happy sight of buildings laid out with the grandiose but now tattered dignity of the once confident European concessions. Sometimes, slapped startlingly between two such buildings, a modern folly gleams with precocious conceit, as flashy as anything you see in Japan.

The shops here are well stocked with both necessities and luxuries, and most heartening of all, the streets are crowded with the young and fashionable out to enjoy themselves.

If you cannot afford, or disdain to patronize, the best hotels (but don’t miss their generous, reasonably priced, breakfasts) you should also avoid the second-rate establishments with their surly receptionists, non-functioning lifts, filthy carpets and crumbling walls. Instead, head for the foreigners’ waiting room at Shanghai station. It contains a rich array of faded upholstery upon which you may happily recline free of both charge and native molestation.

Or (skipping your hotel breakfast) you may take a night train to a suitably distant city, as we did, to Beijing. You may travel “hard” or “soft” seated or prostrate. I found the hard sleeper perfectly restful, but wish that I had filled an old coffee jar with tea for the journey as the Chinese do, and that I had taken some earplugs to block out the loud and uninvited intrusions of the train’s radio system. The soft sleeper is the most luxurious, while the hard seater option remains the preserve of the foolhardy or headstrong.

We met a Japanese fellow called Tetsuya who had travelled alone through Turkey and Iran during the Gulf War, often having to cope with people’s outrage at Japan’s foreign policy. But this experience paled in comparison to what could be the mother of all nightmares, his twenty-two hour journey spent squatting on the floor of a crowded and filthy hard seat compartment. For twenty-two hours he was subject to asinine stares which would grow in number and intensity the moment he showed any sign of life, whether it were to smoke, eat, or merely to scratch his head. The phthisic hawking up of lung linings continued apace, and at regular and not infrequent intervals a comet of phlegm would plunge past his gritted countenance to moisten the grimy floor about or between his feet. He sought escape in sleep until a heightened pungency, a child’s cries and a mother’s rebukes, awoke him to the singular sight of a porcine woman forcing her wretched daughter to defecate on the floor in front of him.

No, thank you very much, there are some paths in this life down which I am quite happy to travel only vicariously.

David Hurley

1991

Part 2 was a (lost) account of my time in Beijing…