This post is based on a lecture I gave to Sekkai O Miru Kai, Hiroshima, 2009.

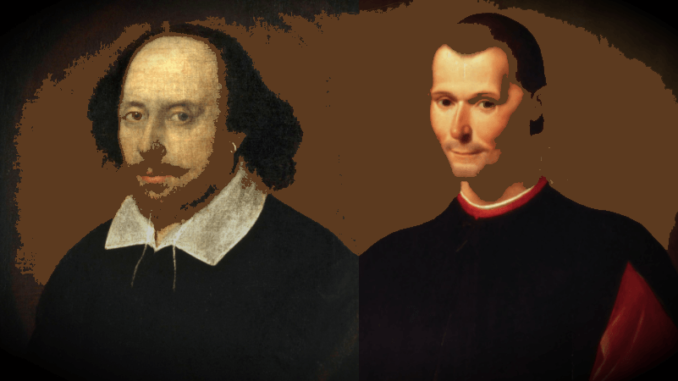

Who Was Machiavelli?

Niccolo Machiavelli was born in Renaissance Florence on 3rd May 1469. The Renaissance was a time of renewed classical learning, of discovered continents and rediscovered manuscripts, progress in the arts and sciences, and the expansion of horizons literally and metaphorically.

Like Leonardo da Vinci, Machiavelli is a good example of a Renaissance Man, a man of many talents; in his life Machiavelli was a diplomat, military commander, historian, political philosopher, poet and comic playwright.

The Renaissance was an exciting time to live, but also a dangerous time. Kings and Popes went to war to increase their earthly power and the city states of Italy struggled to expand or merely to survive. Armies of mercenaries were recruited – and often changed sides – for money, while the invading armies of foreign potentates brought death, destruction and disease.

It was against this background that the Florentine Republic employed Machiavelli as a diplomat and ambassador. This gave Machiavelli the opportunity to travel to and negotiate with the Vatican, the courts of the Kings of France and Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor as well as to other city states in Italy.

Also, in 1502 and 1503, both Machiavelli and Leonardo da Vinci travelled with the infamous Cesare Borgia, as he went on a campaign of military conquest around central Italy on behalf of his father, the licentious Pope Alexander VI.

While the experience of close contact with Cesare Borgia seems to have proved traumatic for Leonardo da Vinci, for Machiavelli, Borgia’s ruthless cunning provided a rich vein of material for his later political writings, most particularly in his lively accounts of Cesare Borgia’s methods in the seventh and eighth chapters of The Prince.

When the Medici family returned to power in 1512, Machiavelli lost his government position. He was briefly imprisoned, tortured with the “strappado”. He refused to confess to the false accusations and was released. Machiavelli retired to his country estate where he devoted himself to his writings until his death in 1527.

Machiavelli’s Shocking Book – The Prince

What was deeply shocking to the religious sensibilities of the time was the way in which Machiavelli separated the pursuit of political power from concerns of religion and morality. In The Prince, his most famous work, Machiavelli offers aspiring princes everywhere a manual for gaining and keeping hold of power.

He does not deny that it is better to be good than evil, but he points out as no-one had done so clearly before, that IF a prince wished to retain his position as a prince it would sometimes be necessary to do evil. Machiavelli sets up an “either – or” proposition and then provides examples from ancient or more recent history to offer empirical demonstrations of the case he is making.

What Machiavelli offers is a lucid, detached, almost scientific perspective on the realities and not the ideals of political manipulation. Yet, his writing is full of vigor and vim. He is passionate about the role of “fortune” which, he calculates, affects about half of human outcomes, but can be countered or even altered through strength of will and precipitous action.

“Machiavel” In England

However, after his death, with the wider dissemination of his work, and its spread into England, Machiavelli the statesman was quickly transformed into “Machiavel” the wicked monster who delighted in achieving power by evil means and in setting wicked traps for his enemies.

The caricature tapped into the English Protestant perception of the innate corruption of Catholic Italy. The wicked Machiavel quickly became a stock stage figure.

There is, for example, Christopher Marlowe‘s scheming Jew of Malta, but it is in the plays of Shakespeare that the influence of Machiavelli is most felt.

Machiavellian Moments In Shakespeare’s Plays

Firstly, there are some direct references to “Machiavel”, such as in The Merry Wives of Windsor, when the Host asks, “Am I politic? am I subtle? am I a Machiavel?”

Secondly, there are the Machiavellian characters, such as Iago in Othello, Edmund in King Lear and of course the eponymous Richard III.

Thirdly, there are plenty of “Machiavellian moments”, especially in the tragedies and histories, but also to some extent in the comedies. Characters who are not innately Machiavellian experience a turn of fortune that confronts them with a choice, often with a need to take swift action. The political realities play out through a process of Machiavellian calculation and a greater or lesser degree of turmoil in the mind of the character in question.

An obvious example would be Macbeth, who is not a Machiavel at the beginning, but is plummeted headlong into Machiavellian considerations by the twists of fortune.

Fourthly, there is Shakespeare’s technique of presentation to consider. Presentation is an important aspect of political success, as we know today when the term “spin” so widely circulates.

How Shakespeare chooses to present his characters is quite often at variance from his sources, as when, for example, Henry V gives his order that the French prisoners be killed, an action which would under normal circumstances be considered treacherous, in the moment of military crises can be managed with a Machiavellian “either – or” structure (either the prisoners are killed or we lose the battle).

This kind of situation typically occurs when the less than appealing actions of a character who is crafted to engage our sympathy must be manipulated by Shakespeare to fulfill his own political agenda.

In this way they can be understood in the light (or dark) of Machiavelli’s The Prince, and the prince of presentation in this case is Shakespeare himself.

David Hurley

Hiroshima

2009

Lecture: Finding Machiavelli And His Ideas In The Plays Of Shakespeare

Also available on Academia.edu: https://davidhurley.academia.edu/research#talks

Thanks, David, for posting this and the accompanying link. I am a writer working on a novel that is steeped in Machiavellian “considerations,” as you term them. This piece has been extremely helpful in fleshing out some dialogue from a central character.

Many thanks,

Neil

Hi Neil,

Thank you for the feedback. Good luck with the novel. Let us know when it is published and available on Amazon!

DH