A Lecture on Shakespeare and Machiavelli, delivered to

Sekai O Miru Kai

Aster Plaza

Hiroshima

April 2009

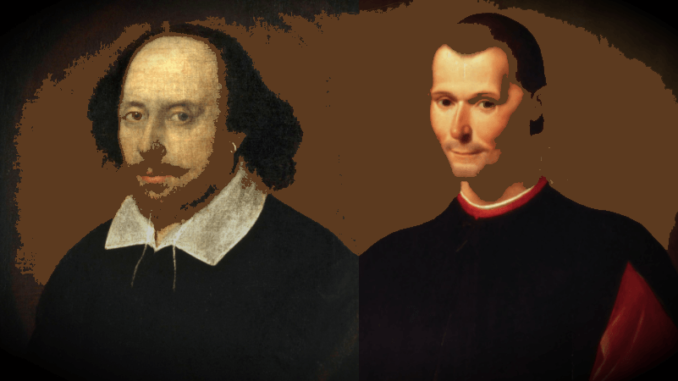

1. The Villainous Machiavel of the English Stage

Eighty-five years after his death in 1527, Niccolò Machiavelli made his first appearance on the London stage in the prologue to Christopher Marlowe’s play, The Jew of Malta, which was first performed in 1592.

This is what he says in the first part of his speech:

MACHIAVEL. Albeit the world think Machiavel is dead,

Yet was his soul but flown beyond the Alps;

And, now the Guise is dead, is come from France,

To view this land, and frolic with his friends.

To some perhaps my name is odious;

But such as love me, guard me from their tongues,

And let them know that I am Machiavel,

And weigh not men, and therefore not men’s words.

Admir’d I am of those that hate me most:

Though some speak openly against my books,

Yet will they read me, and thereby attain

To Peter’s chair; and, when they cast me off,

Are poison’d by my climbing followers.

In today’s lecture we will look at this strange journey, from the political philosopher Machiavelli to the wicked spirit of Machiavel; a journey from Italy across the Alps to France, and then across the English Channel to London and on to the English stage, where he was taken up by Shakespeare and appears throughout his plays in various guises and situations of increasing complexity as Shakespeare lets go of the Machiavel caricature and engages more seriously with Machiavelli the political philosopher.

On the Machiavellian journey from Florence to London via Paris, we will meet several notable characters, namely,

Machiavelli – 1469-1527

Cesare Borgia – 1475-1507

Henry I of Lorraine, Duke of Guise – 1550-1588

Catherine de’ Medici – 1519-1589

John Foxe – 1517-1587

Innocent Gentillet – 1535-1588

Alençon, duc d’Anjou – 1555-1584

Queen Elizabeth I – 1533-1603

Thomas Kyd – 1558-1594

Christopher Marlowe – 1564-1593

William Shakespeare – 1564-1616

2. Who was Machiavelli? – An introduction to his life.

Machiavelli was born 3 May 1469 in Florence. It was a dangerous and exciting time to be alive.

It was of course, the middle of the Renaissance, a time of renewed classical learning, of discoveries in literature, art, science, of voyages and geographical exploration aided by technological innovations.

Just as Leonardo da Vinci is a good example of a Renaissance Man, so too is Machiavelli since in the course of his life he was an historian, a diplomat, a comic playwright, and a political philosopher.

Kings and Popes went to war to increase their earthly power, and the wealthy city-states of Italy were always under threat from rival city-states and also from the intervention of great powers such as France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire. Who could you trust? Alliances continually changed as the situation changed. Professional soldiers, or those who led them, the condottieri, fought only for profit and changed sides without warning… armies brought destruction, death and disease…

The Florence that Machiavelli was born into was a city state that was ruled by an oligarchy run by the Medici family. The Medici family produced three popes, numerous rulers of Florence, and later members of the French royal family. The Medici Bank was one of the most prosperous and most respected in Europe.

Machiavelli was given a humanist education, which emphasized grammar, rhetoric and Latin, and which gave him the foundations of his deep knowledge of Roman history and Latin literature.

Florence had been under a republican government since 1494, when the leading Medici family and its supporters had been driven from power. During this time, Machiavelli thrived under the patronage of the Florentine gonfaloniere (or chief administrator for life), Piero Soderini.

In 1498 Machiavelli was appointed as the Second Chancellor of the Republic of Florence. For the next fourteen years, Machiavelli travelled on diplomatic missions to various Italian city states as well as to the Vatican, the courts of Louis XII in France, Ferdinand II of Aragón, in Spain, and Maximilian the Holy Roman Emperor.

Also, in 1502 and 1503, both Machiavelli and Leonardo da Vinci travelled with Cesare Borgia, the powerful and ruthless son of Pope Alexander VI, as he conquered central Italian territories with audacity, prudence, self-reliance, firmness, and cruelty.

Between 1503 and 1506, Machiavelli was responsible for the Florentine militia and the defence of the city. He distrusted mercenaries, and wanted Florentine citizens to serve as soldiers in defence of their own city, like Romans in the early republic.

Under Machiavelli’s command, Florentine citizen-soldiers defeated Pisa in 1509.

However, in August 1512, the Florentine republic was recaptured by the Medici family, helped by Pope Julius II and Spanish soldiers. Piero Soderini resigned as Florentine head of state, and went into exile.

Machiavelli also lost his job and went to live quietly in his country estate at Sant’ Andrea in Percussina, near Florence.

In 1513, Machiavelli suffered a second misfortune. He was falsely accused of conspiracy against the Medici oligarchy.

He was arrested and tortured with the “strappado”. His wrists were tied behind his back, and he was hung from his bound wrists. This forced his arms to bear the full weight of his body, dislocating the shoulders.

Despite the pain, Machiavelli denied involvement and was released. He returned to his estate, where he devoted himself to his studies and his writing.

What was Machiavelli’s daily life in exile on his estate like?

In a letter to his friend, Francesco Vettori, he writes:

I get up in the morning with the sun and go into a wood that I am having cut down, where I remain two hours to look over the work of the past day and kill some time with the cutters, who have always some bad-luck story ready, about either themselves or their neighbours.

Leaving the wood, I go to a spring, and thence to my aviary. I have a book in my pocket, either Dante or Petrarch, or one of the lesser poets, such as Tibullus, Ovid, and the like. I read of their tender passions and their loves, remember mine, enjoy myself a while in that sort of dreaming.

Then I move along the road to the inn; I speak with those who pass, ask news of their villages, learn various things, and note the various tastes and different fancies of men.

In the course of these things comes the hour for dinner, where with my family I eat such food as this poor farm of mine and my tiny property allow.

Having eaten, I go back to the inn; there is the host, usually a butcher, a miller, two furnace tenders. With these I sink into vulgarity for the whole day, playing at cricca and at trich-trach, and then these games bring on a thousand disputes and countless insults with offensive words, and usually we are fighting over a penny, and nevertheless we are heard shouting as far as San Casciano. So, involved in these trifles, I keep my brain from growing mouldy, and satisfy the malice of this fate of mine, being glad to have her drive me along this road, to see if she will be ashamed of it.

On the coming of evening, I return to my house and enter my study; and at the door I take off the day’s clothing, covered with mud and dust, and put on garments regal and courtly; and reclothed appropriately, I enter the ancient courts of ancient men, where, received by them with affection, I feed on that food which only is mine and which I was born for, where I am not ashamed to speak with them and to ask them the reason for their actions; and they in their kindness answer me; and for four hours of time I do not feel boredom, I forget every trouble, I do not dread poverty, I am not frightened by death; entirely I give myself over to them.

It was in this late period of his life, a life out of power and in exile, that he wrote his most famous and influential work, The Prince, a guide for rulers or for those who want to become rulers, which we shall now discuss.

3. Machiavelli’s Shocking Book – The Prince.

Machiavelli wrote The Prince in 1513, but it was not published until 1532, five years after his death.

The Prince was dedicated to Lorenzo de’ Medici, the ruler of Florence, because Machiavelli hoped to get back into favour with the Medici and be offered a government position.

The Prince was a shocking book because it did not discuss a prince’s actions in terms of moral or religious virtue but in terms of getting, keeping and expanding a prince’s power. The greatest political authority before Machiavelli was Aristotle, and for Aristotle, the state is an instrument for achieving good, and the ruler of the state must therefore be a loyal, capable and good person.

For Machiavelli, a stable state united under a strong ruler is more important, because without firm rule and stable government there will be no peace and no unity. It may be that in order to achieve peace and unity a prince will have to use methods that are not good, methods that may even be harsh or cruel. But if in doing so, he pacifies the people and maintains a unified government, he will have proved himself more virtuous than a good prince whose goodness causes him to lose power and the state to fall into disunity and civil strife.

Machiavelli may be seen, therefore, as a political realist or even as a political scientist, who looks at things as they are, not as people may wish them to be. His work is deeply informed by his knowledge of history and by his own experience as a diplomat, ambassador and military commander for the Florentine Republic.

However, the ultimate purpose of The Prince is to persuade Lorenzo dei Medici to take on the role of liberator of Italy, to be a strong prince, to unite the Italians so that they can free Italy from foreign invaders and make Italy strong again. The Prince ends with a patriotic quotation from Petrarch:

Virtu contro al Furore

Prendera l’arme, e fia il combatter corto:

Che l’antico valore

Negli italici cuor non e ancor morto.Virtue against fury shall advance the fight,

And it i’ th’ combat soon shall put to flight:

For the old Roman valour is not dead,

Nor in th’ Italians’ brests extinguished.

Thus, for Garibaldi and the Italian nationalists of the 19th century, Machiavelli was held up as a great patriot and visionary of a strong, united and independent Italy.

Machiavellian Keywords

Before we look in more detail at the content of The Prince, I want to give you a few Machiavellian keywords:

Virtù – Machiavellian “virtue” – vigorous action, manly decisiveness. Machiavellian Virtù is the decisive action that creates effective government or brings victory to the prince and it is in contrast to traditional Christian or Aristotelian virtue.

Fortune – The unpredictable, womanly force that controls half our lives, and which should be tamed and controlled by Virtù.

Either/or – The reduction of a complex case to a series of binary choices.

Necessity – If A, it is neccessary to B… Advice that transgresses conventional morality is justified in terms of necessity.

Self-sufficiency – A state should never rely on outsiders for its defence.

Policy – A deliberate course of action, often cunning or hidden…

Occasion – A good opportunity, a pretext or excuse, for action…

Audacity – The qualities of audacity, ferocity, impetuosity tend to be preferred above caution and prudence.

The Prince is a relatively short work, consisting of 26 chapters. I will now condense those 26 chapters, consisting of about 32,000 words, to a summary consisting of just 250 words. If you listen carefully, you may understand why Machiavelli’s ideas, expressed so openly and candidly, seemed – and may still seem today – so shocking.

After the summary, I will give you a few key quotations from the book.

THE PRINCE IN 250 WORDS

States are either Republics or Principalities, old or new. Old hereditary states are easy to rule, but to take and hold a new state is difficult, unless you supervise it personally. Old monarchies can be taken, as Alexander took and held Darius’ state, by exterminating the royal family. But states accustomed to freedom must be crushed. It is possible to become a prince, by being well-armed and acting on opportunity. To hold a new state, you must destroy all resistance, using cruelty swiftly and firmly, but benefits should be given little-by-little. The prince must win the approval of the people, and will only be secure when he has his own army. Mercenaries, and other’s armies, cannot be relied on. A prince must study war, read history and know his land. He must appear to be good, but know how to be evil. He should not worry about being thought mean or cruel because generosity will make him poor, and being thought cruel, he will be feared. He should be willing to use cunning and deceit if necessary. He may not be loved, but should avoid being hated. Fortresses are of little use. A prince must be resolute and follow one clear path. He should encourage art and craft, use only capable servants, and keep them under control. He must avoid flatterers. Italy has been lost by indecision. Fortune, like a woman, must be beaten and dominated. Italy needs a strong prince to free her from foreign barbarians.

Reputation of a Prince

Machiavelli was a realist, not a utopian. He writes:

Many men have imagined republics and principalities that never really existed at all. Yet the way men live is so far removed from the way they ought to live that anyone who abandons what is for what should be pursues his downfall rather than his preservation; for a man who strives after goodness in all his acts is sure to come to ruin, since there are so many men who are not good.

Love v Fear, Cruelty v Mercy

In answering the question of whether it is better to be loved than feared, Machiavelli writes in Chapter XVII:

The answer is of course, that it would be best to be both loved and feared. But since the two rarely come together, anyone compelled to choose will find greater security in being feared than in being loved.

Let’s look at the example of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, in Chapter VII:

When the duke occupied the Romagna, it had been governed by weak rulers, who rather plundered their subjects than ruled them, and gave them more cause for disunion than for union, so that the country was full of robbery, quarrels, and every kind of violence; and so, wishing to bring back peace and obedience to authority, he considered it necessary to give it a good governor. So he appointed Messer Ramiro d’Orco, a swift and cruel man, to whom he gave the fullest power. This man in a short time restored peace and unity with the greatest success. Afterwards the duke thought it was not good to give him so much authority, in case he came to be hated, so he set up a court of judgment in the country, under a most excellent president, where all cities had their advocates. And because he knew that the past severity had caused some hatred against himself, so, to clear himself in the minds of the people, and win them over to himself, he wanted to show that, if any cruelty had taken place, it had not been ordered by him, but came from the severity of his minister. Taking proper occasion he brought Ramiro to Cesena, and had him cut in half and left one morning on the piazza with a block of wood and a bloody knife at his side. The ferocity of this spectacle caused the people both satisfaction and amazement.

Machiavelli says that he can find nothing to blame in Cesare Borgia’s methods, since they are the methods that are necessary for anybody who would rise to power.

Later, in chapter XVII, Machiavelli turns back to Cesare Borgia and explains why his selective cruelty is better than too much mercy:

Cesare Borgia was considered cruel; notwithstanding, his cruelty reconciled the Romagna, unified it, and restored it to peace and loyalty. And if this be rightly considered, he will be seen to have been much more merciful than the Florentine people, who, to avoid a reputation for cruelty, permitted Pistoia to be destroyed. Therefore a prince, so long as he keeps his subjects united and loyal, ought not to mind the reproach of cruelty; because with a few examples he will be more merciful than those who, through too much mercy, allow disorders to arise, from which follow murders or robberies; for these are wont to injure the whole people, whilst those executions which originate with a prince offend the individual only.

In What Way Princes Should Keep Their Word: The Man and the Beast

Chapter XVIII

You must know there are two ways of contesting, the one by the law, the other by force; the first method is proper to men, the second to beasts; but because the first is frequently not sufficient, it is necessary to have recourse to the second. Therefore it is necessary for a prince to understand how to avail himself of the beast and the man. This has been figuratively taught to princes by ancient writers, who describe how Achilles and many other princes of old were given to the Centaur Chiron to nurse, who brought them up in his discipline; which means solely that, as they had for a teacher one who was half beast and half man, so it is necessary for a prince to know how to make use of both natures, and that one without the other is not durable. A prince, therefore, being compelled knowingly to adopt the beast, ought to choose the fox and the lion; because the lion cannot defend himself against snares and the fox cannot defend himself against wolves. Therefore, it is necessary to be a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify the wolves.

Fortune

Machiavelli argues that fortune is only in control of half our actions and we have control over the other half. He compares fortune to a torrential river that cannot be easily controlled during flooding season. In periods of calm, however, people can erect dams and levees in order to minimize its impact. Fortune, Machiavelli argues, seems to strike at the places where no resistance is offered, as is the case in Italy.

A prince needs a quality that few have, which is the ability to change as fortune changes. Some men are careful, others are impetuous. When the situation requires care, the careful will be fortunate, but when the situation changes, the careful will be ruined, and vice versa.

Chapter XXV: Fortune is a Woman…

I conclude then that fortune varying and men remaining fixed in their ways, men are successful so long as these two are in agreement, but when they are opposed, then men are unsuccessful. For my part I consider that it is better to be impetuous than cautious, because fortune is a woman, and if you wish to master her it is necessary to conquer her by force; and it is seen that she allows herself to be mastered by the bold rather than by those who go to work more coldly. And therefore, like a woman, she is always, a lover of young men, because they are less cautious, more violent, and master her with more audacity.

4. The Prince In England

Machiavelli’s Il Principe was published in 1532 and placed on the Papal Index of banned books in 1559, but appeared in Latin editions in 1560, 1566, 1680, and 1599.

Machiavelli’s complete works were published in Italian in 1550. In England, publication of The Prince was banned, but the English printer John Wolfe brought out an Italian edition of The Prince and Discourses in 1584, under a false title page claiming it had been printed in Palermo by “Antoniello dei Antonielli”.

Also, Machiavelli’s The Art of War was published in English in 1560, and his Florentine History was published in English in 1595.

Although there was no official printed English edition of The Prince until Edward Dacre’s 1640 publication, earlier English copies circulated in manuscript form among the educated political classes in manuscript form, several copies of which can be viewed in the British Library. Educated Englishmen of the age would have had contacts in Europe with whom they would have exchanged ideas or obtain books, and they would have been able to read Machiavelli in French, Latin and Italian.

Machiavelli was known and discussed by intellectuals throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Sir Francis Bacon and Sir Walter Raleigh among others were keen students of Machiavelli and admired his works.

In the Advancement of Learning, Francis Bacon writes:

… we are much beholden to Machiavel and others, that write what men do, and not what they ought to do . For it is not possible to join serpentine wisdom with the columbine innocency, except men know exactly all the conditions of the serpent; his baseness and going upon his belly, his volubility and lubricity, his envy and sting, and the rest; that is, all forms and natures of evil. For without this, virtue lieth open and unfenced. Nay, an honest man can do no good upon those that are wicked, to reclaim them, without the help of the knowledge of evil.

Here, Francis Bacon is clearly keen to take Machiavelli’s observations and turn them to good use by understanding the ways of the wicked and use that knowledge to protect the good and to convert the evil. Bacon praised Machiavelli for his empiricism, for taking examples from history and turning them into useful knowledge of the ways of men. Bacon was keen to separate the valuable material in Machiavelli from the corrupt and turn it to good use, so the two beasts that he refers to are the serpent and the dove, not the lion and the wolf, and in doing so he is referring his readers to the words of Christ in the Gospel according to Matthew, chapter 10 verse 16:

Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves; Be ye, therefore, wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.

However, the popular view of Machiavelli was that he was the epitome of Italian vice and completely wicked, a corrupter of men.

The Bartholemew’s Day Massacre

This interpretation was influenced not by a direct reading of Machiavelli’s works (which were unavailable to the common people), but by a book which claimed that the French court was under the control of Machiavellian teaching and was responsible for the slaughter of Protestant Huguenots in the infamous Saint Bartholemew’s Day Massacre.

On Saint Bartholemew’s Day in 1572, thousands of Protestants in Paris and elsewhere in France were hunted down and massacred by Catholic mobs.

Here is an extract from Foxe’s Actes and Monuments (commonly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs). From the 16th until the 19th century, Foxe’s Actes and Monuments and The Bible were the two most common books to be found in an Englishman’s home. This is what Englishmen would have read about the massacre:

On the twenty second day of August, 1572, commenced this diabolical act of sanguinary brutality. It was intended to destroy at one stroke the root of the Protestant tree, which had only before partially suffered in its branches. The king of France had artfully proposed a marriage, between his sister and the prince of Navarre, the captain and prince of the Protestants. This imprudent marriage was publicly celebrated at Paris, August 18, by the cardinal of Bourbon, upon a high stage erected for the purpose. They dined in great pomp with the bishop, and supped with the king at Paris. Four days after this, the prince (Coligny), as he was coming from the Council, was shot in both arms; he then said to Maure, his deceased mother’s minister, “O my brother, I do now perceive that I am indeed beloved of my God, since for His most holy sake I am wounded.” Although the Vidam advised him to fly, yet he abode in Paris, and was soon after slain by Bemjus; who afterward declared he never saw a man meet death more valiantly than the admiral.

The soldiers were appointed at a certain signal to burst out instantly to the slaughter in all parts of the city. When they had killed the admiral, they threw him out at a window into the street, where his head was cut off, and sent to the pope. The savage papists, still raging against him, cut off his arms and private members, and, after dragging him three days through the streets, hung him by the heels without the city. After him they slew many great and honorable persons who were Protestants; as Count Rochfoucault, Telinius, the admiral’s son-in-law, Antonius, Clarimontus, marquis of Ravely, Lewes Bussius, Bandineus, Pluvialius, Burneius, etc., and falling upon the common people, they continued the slaughter for many days; in the three first they slew of all ranks and conditions to the number of ten thousand. The bodies were thrown into the rivers, and blood ran through the streets with a strong current, and the river appeared presently like a stream of blood. So furious was their hellish rage, that they slew all papists whom they suspected to be not very staunch to their diabolical religion. From Paris the destruction spread to all quarters of the realm.

The Saint Bartholemew’s Day Massacre was interpreted as part of a ruthless Machiavellian policy of the Catholic Duke of Guise and his family. It seemed significant that the mother of the King of France, who had ordered the killings, was Catherine de’ Medici, a member of the powerful Italian family to whom Machiavelli had dedicated The Prince.

It was the French Huguenot writer, Innocent Gentilet, who influenced the English reaction when he published an attack on Machiavelli, titled Discours contre Machiavel in 1576, which was translated from French into English by Simon Patrick, 1602. Gentilet’s Contre-Machiavel is the first known work dedicated to a full-scale study of Machiavelli. Gentilet believed that Machiavelli’s teachings had influenced the French court and the policy of the Duke of Guise, and had provoked not only the massacre of several thousand Protestants on St Bartholemew’s night.

The 1577 Latin translation of the Contre-Machiavel included a comparison of the Italian Catholic Queen Mother, Catherine de’ Medici (BAD) with the English Protestant Queen Elizabeth (GOOD). In the letter of dedication, commenting on the French translations of Machiavelli, the translator comments,

Satan useth strangers of France, as his fittest instruments, to infect us still with this deadly poison sent out of Italy, who have so highly promoted their Machiavellian bookes, that he is of no reputation in the Court of France, which hath not Machiavels writings at the finger ends, and that both in the Italian and French tongues.

After the Saint Bartholemew’s Day Massacre, English anti-Catholic feeling was very strong, which was unfortunate for Queen Elizabeth who, in 1579, was planning to marry Alençon, duc d’Anjou. He was 24 and Elizabeth was 46. We do not know whether Elizabeth really intended to marrying Anjou, but she was quite fond of him.

The English people, however, were very much against the wedding. They complained loudly because of Alençon’s religion (Catholic), his nationality (French) and his mother (Catherine de’ Medici), who was Italian and Catholic. English Protestants warned the Queen that the “hearts [of the English people] will be galled when they shall see you take to husband a Frenchman, and a Papist… the very common people well know this: that he is the son of the Jezebel of our age”.

5. The Machiavel and Machiavellianism on Shakespeare’s Stage

A reference to Alençon’s ancestor appears in Shakespeare’s early history play, the anti-French Henry VI part I, when Joan of Arc confesses to the Duke of York that Alençon was her lover:

Pucelle: It was Alençon that enjoy’d my love

York: Alençon, that notorious Machiavel!

(V. iv. 73-4)

The English audience would almost certainly have thought of the Alençon who was Elizabeth’s suitor when they heard those lines. Notice that Alençon’s name is tied to Machiavel’s.

This is one of three instances in Shakespeare’s plays where the name of Machiavel appears. The other two are:

1. The Merry Wives of Windsor, when the Host cries to the company,

Peace, I say! hear mine host of the Garter. Am I

politic? am I subtle? am I a Machiavel?(III. i. 104)

2. Henry VI Part III, speaking in soliloquy, Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later Richard III) says:

I can add colours to the chameleon,

Change shapes with Protheus for advantages,

And set the murderous Machiavel to school.

Can I do this, and cannot get a crown?

Tut, were it farther off, I’ll pluck it down.(III. ii. 193)

It is noteworthy that two of these three mentions of Machiavel occur in Shakespeare’s early period, and the third, in The Merry Wives of Windsor, a comedy first performed in 1600 or 1601. Such references require no direct knowledge of Machiavelli. After all, his notoriety was such that a corrupt version of his name could appear in a stage performance without any explanation being necessary. The audience was expected to understand the reference and all that it implied.

Indeed, the London theatre-going audience would have become familiar with theatrical Machiavel types such as Lorenzo in Thomas Kyd’s revenge drama of the 1580s, The Spanish Tragedy. For Christopher Marlowe, as we saw with the opening quotation from Marlowe’s Jew of Malta, the Machiavel character is a stage villain, full of cunning, calculation, wickedness and selfishness, threatening political chaos and disorder.

Beyond references to the name of Machiavel, there are plenty of Machiavel characters in Shakespeare’s plays. Perhaps the three most obvious Machiavels are Richard, Duke of Gloucester in Richard III, Iago in Othello and Edmund in King Lear.

Richard, for example, is represented as a monstrous mis-shapen Machiavel with a hunchback. He delights in evil, secret plots and dissembling. He threatens popular notions of humanity. But he also expresses another aspect of Machiavellianism, a spirited, free dynamism, a love of audacious action. In Machiavellian terms, Richard’s aim is to “attain the position of Prince by villainy” (Prince, VIII).

In other plays characters operate Machiavellian policies or navigate Machiavellian situations. In many cases the characters are not themselves Machiavels, but are forced by necessity, to adopt policies of secrecy, manipulation, audacity, they are forced to use the qualities of the fox and the lion as well as of the man.

Hamlet is one such character. In many ways a sympathetic character and certainly no Machiavel, Hamlet adopts Machiavellian policies of disguise by seeming mad, which gives him an opportunity to observe Claudius, who is a much more thoroughgoing Machiavel character.

Claudius, you will remember, had secretly murdered his brother, married his brother’s wife and sidelined Hamlet, his brother’s heir. Throughout the play Claudius works a Machiavellian policy and plans to have Hamlet murdered in England.

But Hamlet uses Machiavellian audacity when he is on the ship to England with Rosencranz and Guildenstern. He enters their cabin while they are asleep, steals the King’s letter, opens it, discovers that it is an order to have himself killed in England. He then substitutes their names for his, returns the letter, jumps off the ship and swims back to Denmark.

Hamlet describes the action to Horatio in these terms:

Rashly,

And praised be rashness for it – let us know,

Our indiscretion sometime serves us well

When our deep plots to pall, and that should learn us

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough hew them how we will…

(V. ii. 6-11)

In another example of Machiavellian decisiveness, Henry V, a heroic king for the English, alarmed by the possibility that the French will attack his little army again, cries out,

But, hark! What new alarum is this same?

The French have reinforced their scattered men.

Then every soldier kill his prisoners…

(IV. 6. 35-7)

Henry V knows how to use the beast (the lion in this case) as well as the man, as any true Prince should. This is in perfect accordance with Machiavelli’s statement in The Prince that,

Cruelty can be described as well used (if it is permissible to say good words about something evil in itself) when it is performed all at once, for reasons of self-preservation; and when the acts are not repeated after that, but rather are turned as much as possible to the advantage of the subjects.

(Prince VIII)

But, how is it that Shakespeare able to use this unfortunate incident (which he drew from Holinshed, the historian of the Hundred Years war) without damaging the reputation of Henry V?

In Shakespeare and Machiavelli, John Roe suggests the answer is perhaps that Shakespeare himself had learned to adopt a Machiavellian policy of manipulation and presentation of material as a playwright. The scene in Henry V ends immediately after Henry gives the order to kill the prisoners and in the very next scene we learn from two soldiers in the English army, Fluellen and Gower, that the French have attacked the English baggage and killed the young boys who were left with it. Moreover, Gower tells us that, this was the reason why Henry V gave the order to every man to cut his prisoner’s throat, and concludes “O, ‘tis a gallant king”. Later in the same scene he tells us that Henry V is not like Alexander the Great because “he never killed any of his friends”, just as Cesare Borgia is not like Agathocles in Machiavelli’s The Prince, because Borgia only killed out of political or military “necessity”, whereas Agathocles delighted in killing for its own sake, according to Machiavelli.

We discover by this scene that Henry V only kills in cold blood if it is necessary to do so for survival, or in revenge, and he will only kill his enemies, whereas the French are portrayed as ruthless child killers. The effect of this presentation is to make Henry seem better and to make ourselves feel better about Henry. It is pure manipulation of presentation and of our response on Shakespeare’s part.

Of course, whether or not Shakespeare actually read Machiavelli or simply picked up Machiavellian ideas from the conversations going on around him is something we do not know, but there is so much Machiavellian material in his plays that we can say with some certainty that The spirit of Machiavelli did indeed travel from Italy, across the Alps, through France, over the English channel and entered into the plays of Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

Shakespeare and Machiavelli (Studies in Renaissance Literature)

Dates

1431 Rodrigo Borgia (Pope Alexandar VI) born.

1452 Leonardo da Vinci born.

1464 Cosimo de Medici died.

1469 Machiavelli born. Lorenzo the Magnificent, ruled, 1469-1492

1490 Savonarola becomes prior of the San Marco monastery

1494 French army of Charles VIII in Florence. Piero de Medici exiled. REPUBLIC SET UP

1497 Bonfire of Vanities.

1498 Savonarola burned.

1503 Pope Alexandar VI died.

1507 Cesare Borgia killed in Spain.

1512 Piero Soderini exiled. Medici return to power with aid of Spanish troops.

1513 Machiavelli given the strappado.

1519 Lorenzo died. Leonardo da Vinci died.

1527 Machiavelli died.

1532 The Prince published in Italy.

1564 Shakespeare born.

1572 The St Bartholemew’s Day Massacre

1576 Innocent Gentilet’s Discors Contre Machiavel published.

1582?-87? Thomas Kyd: The Spanish Tragedy

1589 Christopher Marlowe: The Jew of Malta

1590 Shakespeare: Henry VI, parts I-III

1592 Shakespeare: Richard III

1616 Shakespeare died.

1640 The Prince published in English.

Our monthly literary journal “Inostrannaya Literatura” (Moscow, Russia) would like to publish the Russian translation of your lecture on Shakespeare and Machiavelli (delivered to Sekai O Miru Kai-Hiroshima, April 2009). I am addressing you in the hope that you will be so kind as to grant us a permission on serial non-exclusive rights.

Our journal is considered one of the most prestigious literary journals in Russia, that has existed in the Russian bookmarket since 1955, the titles and the names appearing forthe first time on its pages are often selected by major publishing houses.

The authors we have so far featured in translation: Jose Saramago, Gunter Grass, Kendzaburo Oe, Graham Swift, Didier van Cauwelaert, Umberto Eco, Milan Kundera, Peter Ackroyd, John Hoyer Updike, Irvine Welsh, Aldo Nove, Muriel Spark, Orhan Pamuk, Michel Houellebecq and many others.

We are a non-commercial journal distributed by subscription throughout Russia,a major part of the copies goes to the public libraries. Thanks a lot for your attention.

Publisher: ANO Redaktsiya jurnala “InostrannayaLiteratura” (Foreign Literature)

Publication date: 2016

Number of pages: 288 (in the journal)

All formats in which publication will be published: paperback, serial publication

List price of publication in each format: 6-9 USD (depends of the seller)

Lifetime print-run of publication in each format: 2500 copies

Territory of distribution: Russia

Language: Russian

Brief description of the context in which the work will be used in publication: the issue of the journal consecrate to the foreign literature

Best regards

Hello Milda Sokolova,

Thank you for contacting me. I have sent an email to discuss your proposal.

Best wishes,

DH

I read your article and I find it fascinating, the way shakespeare wrote his plays , and how constantly he puts Machiavellivin the spot. my question is : What is the purpose of Shakespeare to put Machiavelli, and his ideas, along with portions of the Prince in his play? Was he fascinated by it? Did he despite Machiavelli? Or perhaps he was not as great as people claim he was?

Marisol.