From Shanghai to Beijing the countryside is low-lying, monotonous and heavily cultivated, with paddy fields flanking the Yangtse, tobacco and wheat fields farther north. Everything changes with the arrival of the wall-topped mountain ranges north of the capital. They are far removed from the upturned onigiri mountains of Japan, being more akin to loaves of bread, well risen and mouldy with age. As these mountains recede they give way to broad expanses of semi-steppe over which the sun sinks with interminable leisure.

We had left the clouds down over drab Beijing. The shadow of our train stretched farther and farther across the Gobi plateau, reaching for the distant ripple of hills beyond which lay the scattered communities of husbandmen whose goat herds bind them with strands of purest cashmere to the woollen mills and curry houses of Bradford.

It takes about a day to get to Ulaanbaatar, which includes a three hour nocturnal halt at the Chinese-Mongolian border during which time the train is overhauled. It was here, on a featureless border post station that I felt the first benefit of my duck-down great coat, purchased at Beijing and, perhaps, stuffed with the same. It was not yet autumn, but the nights felt colder there than they have done here in the middle of an albeit mild Berlin winter.

The station was not completely devoid of distractions, and while the other members of the party headed single-mindedly for the bar, I decided to indulge in a little stocking up; something which I had not bothered to do up until then. Nor had it been particularly necessary as the Chinese train’s dining staff had gone about their duties in a reasonably orderly fashion, doling out bowls of noodles, rice and so forth from a well furnished, if uninspiring, larder. I thought it prudent, however, to forearm myself against the uncertainties of the Russian leg, so to speak, and purchased the better part of the station kiosk’s supply of Ritz biscuits, that is to say, five packets.

Ulaanbaatar

By the time we arrived at Ulaanbaatar two packets had been disposed of over several rounds of rummy. Then, jumping down onto the tracks and pushing my way through the throngs of gaily clad Ulaanbaatanians, I was accosted by an elderly native whose still beady eyes had taken in the three tell-tale red cylinders visible through my Korean Airlines carrier bag. He pushed a few filthy banknotes into my pocket. I resisted his advances for the space of thirty paces before yielding to the fellow for a handsome loss – my second thus far on the journey. Age has not afforded so gracious a dispensation to the fellow’s memory as it has to his eyes, for no sooner had he stuffed my biscuits down his jacket than he forgot all about the train and beetled off in the opposite direction.

The tented capital of Outer Mongolia eventually settled on its present site in 1639, cloistering around the Da Khure and other monasteries. It was still a “City of Felt” seventy years ago when Damdiny Suhbaatar’s revolutionary forces took power and renamed it Ulaanbaatar, or “Red Hero”. Even today wooden fences mark out boundaries behind which peripheral tent dwelling communities live, eking out an existence which has little to do with the romantic pursuit of traditional simplicities.

A century of two ago a traveller from China would have seen Ikh Khuree – as Ulaanbaatar was then – as an integral part of the northern desert and the Hentiyn Nuruu highlands beyond. Today, however, the city seems rather to spit in the face of the land which has nurtured it, having imposed itself upon the desert as an alien and adversative presence, a sprawling array of flats and factories. In the middle of the city the government building, cumbersomely Palladian, sits amid a grandiloquently expansive central square, an urban desert not blessed with the far richer emptiness of its counterpart in nature.

Revolution

But then, a century or two ago the said traveller would probably have been in the service of a Manchurian overlord keen to impose upon his subjects an exquisite variety of tortures lest they forget to whom they owed obeisance. So the upheavals which led to the Mongolian revolution are seen as a patriotic as much as a communist victory, a revolt against the feudal yoke of Manchurian hegemony, and the leader of the revolution, Suhbaatar, may well survive in the Mongolian memory as a national hero.

The Mongolian revolution was, however, a Soviet sponsored affair, and with the collapse of that empire Mongolia finds herself once again independent, yet balanced and landlocked between China and Russia and unable to develop without the cooperation of either. The retreating Soviets left behind them economic and environmental decay, and yet so much of Mongolia

remains untouched that her new leadership (that is, old politicians in new clothes) is faced with the challenge of not whether but how to develop her resources.

Siteseeing & Shopping

If you should come this way you should not miss an opportunity to visit the city museum which displays an impressive array of artifacts detailing the wealth of Mongolian history and its extensive resources; animal, vegetable, mineral and – in its Lama Buddhism – abstract. It is as much here as anywhere else that one realizes both the potential and the risks faced by a developing Mongolia, for there is so much to offer, and so much to lose.

At the moment, however, the economy remains rheumatic. The shops are not empty, selling plenty of nothing-much and little in the way of fruit.

Away from the centre of the city there is a large market place where the buyers and sellers mingle together in one amorphous crush. There are no stalls, except along the far edges of the market, and the sellers simply wear or hold up their goods so that one is forever propositioning and being propositioned.

Once it is discovered that a Western punter is sniffing around for a bargain, such as a fox-fur hat for example, a cornucopia of possibilities appear before him as the smell of his desire spreads on the air. Beefy women pull diverse examples from carrier bags; a grey fox-fur to the left, a white one to the right, a brindled fox-fur from on high, a red fox-fur thrust over from behind, docked or with brush attached, ear flaps flapping or tied back, fat fluffy foxes that seem to inflate the wearer’s head, or more demure numbers that sit petite above the ears. Leather jackets and boots are also in plentiful supply and the rigmarole of taking off and putting on draws the milling masses into little eddying circles of onlookers. Their curiosity had a more restrained quality about it than that of the gawking Chinese. They didn’t stop in their tracks and stare with goggle-eyed, open-mouthed imbecility, but seemed more receptive to interaction as if realizing that they too were on display and subjects of curiosity.

Young & Old

Despite the uncertainties of the economy a significant number of young people seem to have money to spend and access to Western fashions. They also know where and when the good things are to be had, cleaning out the restaurant in which we were dining of its sweetmeats before we had got past the goulash.

“Ah, they live off their parents,” muttered Tsernnadmidyu Bulgantamir, a former party functionary turned entrepreneur, while his long suffering father struggled at the wheel of their car. “They aren’t interested in the old ways. They don’t want to work.”

“How can they afford to buy clothes and dress smartly if they don’t work?” asked my Canadian friend, a former helicopter pilot who had charmed his way into Bulgan’s confidence.

“Their parents…” What he was about to say was lost in the desperate howl of the engine as we endeavoured to move off on our tour around off-beat Ulaanbaatar.

In spite of Bulgan’s pessimism about Mongolia‘s youth, “The Old Ways” are still very much in evidence. It is not to be remarked upon if some fellow perched proudly on his pony hails in from the countryside, straight-backed and clad in a brightly sashed ultramarine overcoat, calf-length boots and a felt trilby, for there are many urban Mongolians who go about in similar apparel.

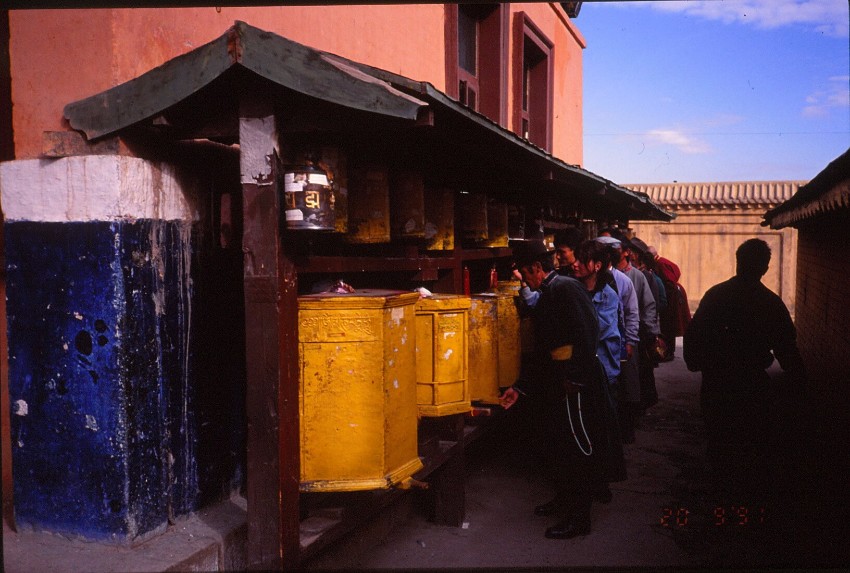

“The Old Ways” also appear to be doing quite nicely thank you at the monasteries we visited, both at Bulgan’s brother’s place (a modest set-up of circular prefabricated huts) and at a much larger, wealthier establishment which was undergoing renovation and having the roof of its main temple gilded. Children seemed as much a part of the life of these monasteries as the saffron-cloaked monks, many of whom were little more than boys themselves. Locals lined up to spin oil drums which had been set up on vertical axles and cunningly painted up to resemble prayer-wheels, while an aged monk ignored the hoo-haa of work and prayer to expand upon the scriptures for the edification of a sashed and overcoated lady of similar antiquity.

The Mongolian branch of Buddhism, which is related to that of Tibet, is as keen on exuberant patterns and designs as the Korean variety, and almost as fond of the green paint pot, though the application of its contents is of a lighter, more sun-bleached, less assertively prismatic hue, such as one seldom sees elsewhere.

Once we had consumed most of Bulgan’s father’s weekly petrol ratio, forced a few dollars into Bulgan’s outstretched hand and a couple of packets of Marlboroughs into his father’s pocket, we bade farewell and saw them off with a ceremonial shove of the car which lurched into a spluttering semblance of life and disappeared behind a trailing miasma of exhaust fumes.

Hotel & Yurt

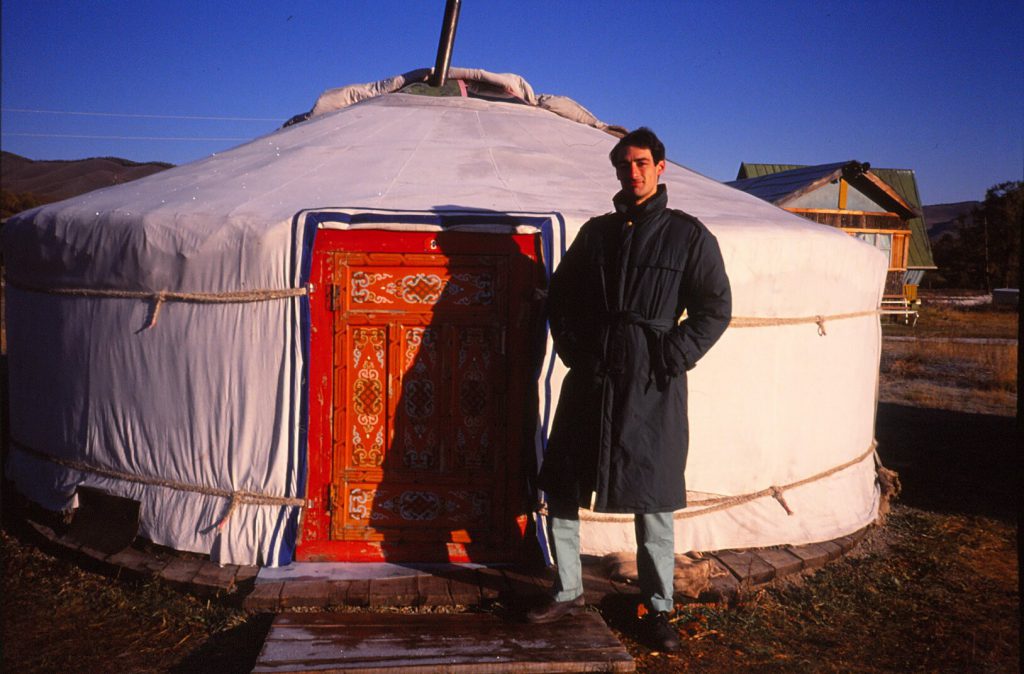

We stayed at an hotel about sixty miles into the hills beyond Ulaanbaatur. Apart from the hotel there was an administration building, a primary school, a few blocks of flats and a scattering of yurts.

A yurt is the traditional Mongolian dwelling, a round tent of canvas and felt (or, for the potentates of yore, leopard skins) which is supported on a framework of uprights erected over a wooden floor. The roof section of the framework resembles a giant cartwheel with its hub pushed skywards. You enter by way of a five foot high doorway and are confronted by a wood-burning stove the smoke of which is directed by way of a tin funnel through an opening in the center of the roof – only other orifice in the yurt apart from the door. The Mongolians are, you see, a passionate people, not given to half measures; either they are out or they are in and done with it – no languid gorping through windows at the outside world from the warmth and comfort of indoors.

Just so, they are here one minute and gone the next, lock, stock and barrel, and not an hoof left behind etc., only a round patch of flattened soil where once a yurt had proudly stood.

There were a few yurts going spare at the hotel so we were able to enjoy the best of both worlds; the bucolic delights of the nomad and the perks of the party cadre, not the least of which was the ample dinner served up by the hotel restaurant.

We were joined by some of the Old Comrades who cut quite a collective dash until, that is, they plonked their executive briefcases one after the other onto the bar, opened them up and had the bartenders fill them with bottles of the local brew.

The local brew, I might add, was quite a bargain, being just as damaging as the more illustrious brand names that were available but only costing a third of the price.

And thus it came to pass that, after a convivial imbibing, an unsteady yurt-ward tottering ensued, a snuggling beneath the eiderdown followed therefrom on and at last a sinking into sweet forgetfulness until, at some unearthly hour, the maid, rosy cheeked and dew lapped with the freshness of dawn came crashing into the yurt with a bucketful of logs and raked and lit the long-expired stove.

David Hurley

1991