On Wednesday evening I was reading Clive James’ translation of the 25th Canto of Dante’s Purgatory with my private student Dr. M and was struck by the curious convolutions of the passage on the generation of the human soul.

To put it in its context, Virgil is leading Dante through Purgatory when they encounter (in Purgatory 21) the newly redeemed shade of “Stazio,” i.e. Statius, a first century Roman poet. Statius accompanies his fellow poets through the rest of Purgatory, and continues with Dante into Paradise after Virgil, a virtuous pagan who is unable to enter Paradise with them, turns back.

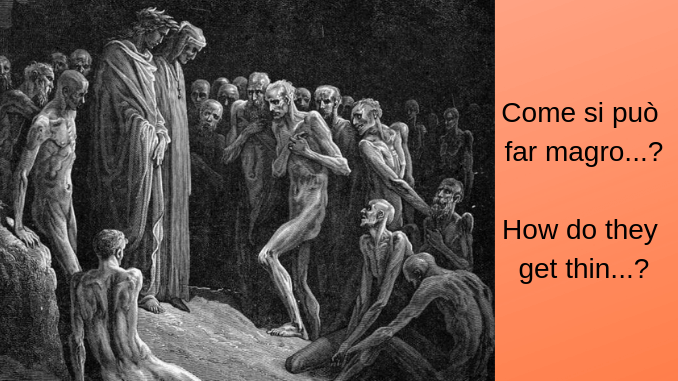

How Is It That The Shades Of The Dead Get Thin?

Dante is itching to ask Virgil how it is that shades get thin when they don’t need to eat. Virgil hands the job over to Statius, probably because what follows is a late medieval Christian account of the creation and “ensoulment” of a human being and then what happens to the human soul after death and how it is that a shade may indeed seem to lose weight although it is no longer embodied. (I was going to refer to the account as “Thomistic,” i.e. following the teaching of Thomas Aquinas, which I do not think is incorrect, but see this paper for arguments around that issue.)

Virgil’s Accidental Conversion Of Statius

Dante represents Statius’ as one who, by reading Virgil’s poetry (i.e. his fourth Eclogue), is inspired to convert to Christianity, something which was impossible for Virgil to do or even to conceive of doing, as he died approximately two decades before the incarnation of Christ. His conversion of Statius is an ironic accident, since he, the greater poet, neither knew of Christ or Statius, or the need for conversion and baptism.

There is no evidence that Statius himself ever converted to Christianity, although he is fabled to have been secretly baptised. However, one of his functions for Dante the poet is to provide Dante the character with a Christian guide as they ascend the higher levels of Purgatory and approach Paradise, for the closer the they get to Paradise the less authoritative the pagan Virgil becomes.

Clive James’ Translation of Dante

So we come to Statius’ account of human generation, as translated by Clive James.

For the most part I have enjoyed reading Clive James’ translation-and-interpolation as his use of ABAB(A) rhyming quatrains (with extra lines where needed) and an insistence on masculine rhymes give it a briskness of pace even if the interpolation slows down the narrative drive by stuffing in extra words, phrases and lines.

However, James’ version of Statius’ explanation left me scratching my head. Late medieval accounts of bodily functions such as digestion, blood flow and generation may seem strange to us, but they are not difficult to grasp if they are clearly explained.

Dante’s poetic account may seem obscure if we do not know, for example, that, following the teaching of Galen (130-210 AD), it was believed that blood is the product of digestion.

Galen’s Theory of Digestion

According to Galen, after the stomach has broken down food into chyme, it moves to the bowels where it is decomposed. Next it is transported to the liver thanks to the sucking ability of the portal vein. The liver turns the food into dark blood, which then enters the heart.

Note, Galen knew that there were both veins and arteries and he inferred that they had two different functions. Veins carried ordinary blood from the liver for the replenishment of the various parts of the body. Arteries, however, carried a brighter (“perfect”) blood that was generated in the heart and arteries from inhaled air and exhalations of the humours (one of which is, er, blood) and invigorates the body with a “vital spirit.” (See G. E. Lloyd’s Greek Science Chapter 18.)

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = “clevercuckoon-20”; amzn_assoc_ad_mode = “manual”; amzn_assoc_ad_type = “smart”; amzn_assoc_marketplace = “amazon”; amzn_assoc_region = “US”; amzn_assoc_design = “enhanced_links”; amzn_assoc_asins = “0393007804”; amzn_assoc_placement = “adunit”; amzn_assoc_linkid = “61a17ba545ccf54a8210f57838314c57”;Avicenna’s Stages of Digestion

This scheme is taken up by Avicenna, who describes digestion as having four stages ( source ):

- Digestive Stage 1: Food is turned into chyle in the stomach and intestines.

- Digestive Stage 2: Chyle begins to be transformed into blood in the liver.

- Digestive Stage 3: Dark blood is purified of its superfluities and converted into “perfect blood” in the veins.

-

Digestive Stage 4a: Perfect blood goes to nourish the heart and brain.

- Digestive Stage 4b: Some of perfect blood is retained in the heart and receives a “formative virtue” (its creative power).

- Digestive Stage 4c: That perfect blood informed with a formative virtue is purified into sperm.

On Human Generation and the Soul

In males, as seen above, the digestive process reaches its highest stage when “perfect blood” has been purified into semen. It then mingles with female “blood” in the womb creating what Dante’s Stazio refers to as a “vegetative soul” (the “plant” stage) which develops into a “sensitive soul” (the “sea-sponge” stage) and then has a “spiritual soul” implanted directly by God.

This is a medieval Christian modification of Avicenna’s version of Galen’s teaching. It follows the three divisions of the soul as expounded by Thomas Acquinas, following Aristotle’s teaching in his De Anima. Galen himself taught that plants possess a physis – a “nature” – but not a psyche – soul. Animals, unlike plants possess both a physis and and psyche:

Since feeling and voluntary motion are peculiar to animals, whilst growth and nutrition are common to plants as well, we may look on the former as effects of the soul and the latter as effects of the nature. And if there be anyone who allows a share in soul to plants as well, and separates the two kinds of soul, naming the kind in question vegetative, and the other sensory, this person is not saying anything else, although his language is somewhat unusual. We, however, for our part, are convinced that the chief merit of language is clearness, and we know that nothing detracts so much from this as do unfamiliar terms; accordingly we employ those terms which the bulk of people are accustomed to use, and we say that animals are governed at once by their soul and by their nature, and plants by their nature alone, and that growth and nutrition are the effects of nature, not of soul.

Galen, On the Natural Faculties, trans. Vehling, pub. Loeb. Online Source

Now, without needing to go any further into Galenic and Thomist hypotheses of the soul, let’s look at the passage from Purgatorio 25 in Dante’s original, then Clive James’ poetic translation and then A. S. Kline’s modern prose translation. That will set us up for a discussion of Clive James’ translation in tomorrows blog post.

Dante’s Purgatorio 25, Lines 37-66

Sangue perfetto, che poi non si beve

da l’assetate vene, e si rimane

quasi alimento che di mensa leve, 39prende nel core a tutte membra umane

virtute informativa, come quello

ch’a farsi quelle per le vene vane. 42Ancor digesto, scende ov’è più bello

tacer che dire; e quindi poscia geme

sovr’altrui sangue in natural vasello. 45Ivi s’accoglie l’uno e l’altro insieme,

l’un disposto a patire, e l’altro a fare

per lo perfetto loco onde si preme; 48e, giunto lui, comincia ad operare

coagulando prima, e poi avviva

ciò che per sua matera fé constare. 51Anima fatta la virtute attiva

qual d’una pianta, in tanto differente,

che questa è in via e quella è già a riva, 54tanto ovra poi, che già si move e sente,

come spungo marino; e indi imprende

ad organar le posse ond’è semente. 57Or si spiega, figliuolo, or si distende

la virtù ch’è dal cor del generante,

dove natura a tutte membra intende. 60Ma come d’animal divegna fante,

non vedi tu ancor: quest’è tal punto,

che più savio di te fé già errante, 63sì che per sua dottrina fé disgiunto

Dante, Purgatorio 25, 37-66

da l’anima il possibile intelletto,

perché da lui non vide organo assunto. 66

Clive James’ Translation

Here is Clive James’ translation with some words placed in bold, or in bold and italics, to help clarify what the pronouns are referring to.

The thirsty veins do not

Drink perfect blood, which, sharing the pure state

Of food kept from the table, takes in what

The heart confers, the power to generate

The future body’s parts. Like blood that takes

The standard course through veins to fashion these,

The perfect heart’s blood subsequently makes

Its way down to where words are bound to please

Less than a decent silence, and from there

It joins another’s blood in the right place,

The natural vessel. In this way the pair

Of matched streams mingle as they share the space:

One passive, and the other, since it flows

From sheer perfection, active. The twinned stream

Begins to function as its thickness grows,

Coagulating, quickening its seam

Of virtue into potent readiness—

A soul, much as a plant’s, but not the same,

Because the plant’s soul sets out never less

Than all set to arrive, whereas the frame

Of this soul is sea fungus at the most.

It moves, it feels, it goes on to produce

Organs for faculties. It is the host

Of every little thing and each thing’s use

That grows out of its seed. And now, my son,

The force unfolds and spreads out of the heart

Of the begetter, until all is one,

And nature has made shift for every part

And member. But you can’t see how it’s done

As yet—quite how from the dumb animal

A creature comes that speaks—and neither could

A wiser one than you. He saw it all,

Except one special part that would come good

And be the mind. No, Aristotle thought

The intellect was separate from the soul

And common to all men, and so he taught.

Dante, Purgatory 25, 37-66, translated by Clive James

If you are not familiar with Galen or Avicenna’s theories, then much of the first half of the quoted section is almost certainly incomprehensible, even though one of Clive James’ rules of thumb is to incorporate explanatory notes into his translation. For more on this, see my next blog post in this series.

A. S. Kline’s Prose Translation: A Study In Clarity

To illustrate my point, compare James’ translation with A. S. Kline’s modern prose translation. I contend that the meaning is clearly conveyed and can be comprehended without any prior knowledge of Galen or Aquinas.

Perfect blood, which is never absorbed by the thirsty veins, and remains behind, like food you remove from the table, acquires a power in the heart sufficient to invigorate all the members, as does the blood that flows through the veins to become those members. Absorbed again it falls to the part, of which it is more fitting to be silent than speak, and, from that part, is afterwards distilled into the partner’s blood, in nature’s vessel. There one blood is mingled with the other’s: one disposed to be passive, the other active because of the perfect place it springs from: and mixed with the former, begins to work, first coagulating, then giving life, to what is has formed for its own material.

The active power having become a spirit, like a plant’s, different in that it is developing, while the plant’s is developed, now operates so widely that it moves and feels, like a sea-sponge, and then begins to develop organs, as sites for the powers of which it is the seed. Now, son, the power that flows from the heart of the begetter, expands, and distends, into human members as nature intends: but you do not yet understand how it becomes human, from being animal: this is the point which made one wiser than you, Averroës, err, so that he made the intellectual faculty separate from the spirit, because he found no organ that it occupied.

Dante, Purgatory 25, 37-66, translated by A. S. Kline

In tomorrow’s blog post I will look at the first few lines of this passage of Dante’s Purgatorio and the problems of Clive James’ translation in more detail.

DH

P. S. This topic is continued in this blog post: Si Rimane Quasi Alimento Che Di Mensa Leve