After leaving Hawai Onsen Roland and I caught the train to Matsue. While staying at the Mido Resort onsen ryokan was definitely the highlight of our trip, the couple of days we spent in Matsue were not devoid of entertainment, and Matsue Castle remains the most beautiful castle I have seen in Japan, with the faithfully renovated castle at Matsuyama in second place.

Photo: Entrance ticket for Matsue Castle, and brochure for Lafcadio Hearn’s House.

The next day was grey and wet and we went on to Matsue, which at first seemed quite a bland and unattractive provincial town.

We headed up the hill to the castle and stopped for lunch at one of the little souvenier shops. It turned out that little more than cold noodles were on offer. Still, the climb was well worth it as the castle is one of the few that has remained intact, with original wooden interiors and no sign of concrete or lifts.

Lafcadio Hearn

Lafcadio Hearn was a late – very late – romantic writer who settled in Japan in 1890 and wrote flowery screeds about the old traditions that were giving way to modernization. Even before our trip to Matsue, Hearn’s overwrought prose had provided us with a great deal of entertainment as we competed to outdo each other in exaggerated Hearnisms, usually involving the insertion of the word “prismatic” into whatever concocted absurdity we could come up with.

For all that, I have a soft spot for the old boy, who, after all, was a forerunner of ourselves, turning up in Japan and making a living of sorts as an English teacher, and becoming a celebrity merely by BEING HERE. It was after he published a few books in praise of the beauty of Japan that his apotheosis into the Japanese pantheon of gods and heroes occurred.

At the castle we had a foretaste of Lafcadio Hearn‘s prose. A Plaque quoting Lafcadio Hearn enthusing about the flight of egrets from the lofty topmost eaves of the castle.

Lafcadio, a half-Greek Irishman, is more or less worshipped all over Japan as the great master of English prose who should be studied “both for content and form.”

He lived in Matsue for about a year and a little later in the day we descended the hill, walked along the moat with its overhanging trees until we came to an unspoiled row of samurai homes. Lafcadio lived in one of these, and there is a museum to commemorate him.

We passed through the portals of the gate and came to a “five sided lantern” accompanied by an amusing legend. The lantern was in commemoration of the solemn occasion of the handing over of some of the deceased writer’s hairs, which I suppose have now been enshrined.

This fellow, who was so full of the wonders of Japan, the “blanched roads,” “prismatic skies,” “faded colours” etc was, we discovered, blind in one eye and myopic in the other. He had a table specially constructed so that his papers would be no more than five inches beneath his nose, which is, incidentally, an ideal height for one to rest one’s head so as to enjoy a prolonged snooze. His wife didn’t seem to divine the potential that desk afforded for a postprandial “pisolino,” and attributed his not noticing her presence to his absorption in his writing.

That evening we arrived at our hotel nearly an hour late, having taken the wrong road.

Grand Hotel Suitengoku

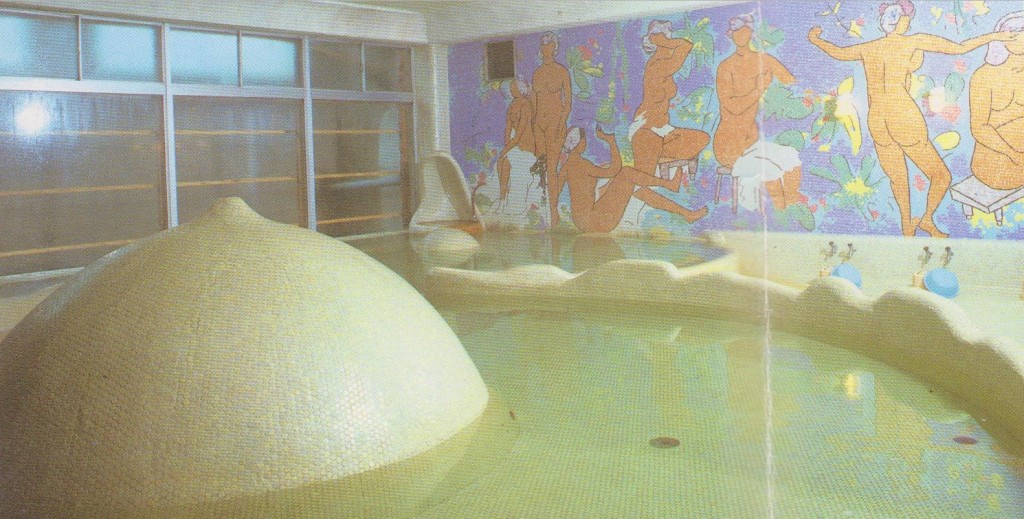

I think this photo of the bath house, taken from the old brochure of the Suitengoku – or “Grand Hotel Water Paradise” – says it all:

The bath was the strangest one yet. One wall was covered in a frieze of naked ladies and in the bath itself a breast-shaped hill reared up out of the water, and a bath within the bath was shaped like a pair of lips. In one corner there was a cabin in which you could curl up and steam. The wall of the bath curved wildly and the whole expanse was overlaid with round marble button-sized tiles. It had a distinctly jaded and rather seedy appearance, especially after the bath-house at Hawai Onsen.

There was once again an abundance of crab for dinner.

A couple of Frenchmen and a little boy were in the bath the next morning. The little boy came up to me and tugged at my yukata. That was about the only exchange between us, but we were to meet again in rather amusing circumstances…

Breakfast was served in a large tatami room. Roland and I wandered in around eightish. “Ah, gaijin,” thought the ladies, and placed us accordingly. There were, however, four cushions and four little tables and a couple of white cushions to one side. We thought nothing of this and tucked into our breakfast as soon as it came. It then occurred to us that we had probably been directed to somebody else’s place. I found a room ticket which confirmed this and we bet that it would be the French (who Roland insisted were Czech or something), and that they would be a party of two men, two women, a boy and a little girl. Roland was a bit edgy about being caught out but I was determined to finish my breakfast in as leisurely a manner as befits a holiday.

The serving ladies seemed nervous but were too polite to approach us. I polished off my dried seaweed and we were invited to go onto the dias to drink some green tea, for which Matsue is famous.

No sooner had we positioned ourselves on the little dias when the ladies fell upon our breakfast things and set about restoring the settings to their pristine state as fast as their kimonos and etiquette permitted. Scarcely had they started on their discreetly executed rescue operation when our French friends entered the hall, barely thirty seconds after we had left their places. This is where kimono-clad excellence really came into its own. The unsuspecting continentals were ceremoniously welcomed to the hall and then, in a sudden yet seamless departure from form, they were unwittingly guided to join us and partake of the tea ceremony BEFORE breakfast.

By the time we left, order had been restored and the French were none the wiser.

It was another wet day. We tramped back to the Samurai Quarter to visit Lafcadio’s house – which proved to be as fruitless as the museum. As you enter you go through the usual routine of taking off your shoes, but even this has been turned into an opportunity to sacramentalise the Great Master’s memory. A notice instructs us to remove our shoes “just as Lafcadio did every time he entered.” Gasp!

It is a pleasant house, just what you’d expect from a little samurai place, with tatami mats, low ceilings, shoji and exquisite little gardens on each side. Hearn managed to write page after endless page about it.

A Japanese tour group entered the venerable building shortly after we arrived and took great delight in enjoining us not to bang our heads on the cross beams. They stayed for about five minutes. Just before we left some Americans came in and one of the passed the most pertinent of remarks so far heard about the Hearn cult. He wandered in, sniffed the air for a second or two and asked, “What have we come here for? It’s just like our hotel room.”

I left with precious treasure – selections from Hearn’s myopic “Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan,” which has provided us with a great deal of amusement ever since.

I have been unable to find any reference to the Grand Hotel Suitengoku on the Japanese or English search engines and I am not really surprised. I expect it has gone the way of the Mido Resort because it already seemed dated when we stayed in 1991, two years after the Japanese Bubble burst. I cannot think such an establishment could survive the lean years that followed.

So we too had our own “glimpses of unfamiliar Japan,” which the stream of Time has washed away.

David Hurley