I recently finished reading David Boyd’s lively translation of The Factory by Oyamada Hiroko, a contemporary Japanese writer of somewhat dystopian novellas who, incidentally, lives barely a stone’s throw from me somewhere in the western suburbs of Hiroshima.

One of my English language students told her classmates and me about another of Oyamada’s novellas, “The Garden,” and I was intrigued enough to look her up on Amazon.

It turns out that so far only one of her works, The Factory, has been translated into English. I bought the Kindle edition and enjoyed reading it thanks largely to of David Boyd’s translation. His rendering of the opening chapter quickly had me chuckling and drew me into the action. I especially enjoyed the narrator of the first chapter, Oyamada’s tart female observations of the people she encounters at and through “the factory,” especially of the other women.

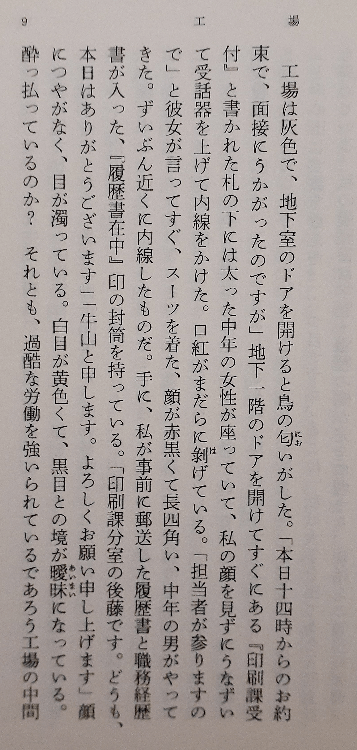

A month later the same student brought in her Japanese edition of The Factory – “Kojo” in Japanese – and as I had my Kindle with me we were able to compare the Japanese with David Boyd’s translation. It was quite an eye-opener, how he cuts through to the meat and finds a way to convey it into English that flows with a deft economy where it needs to, but also brings you up short with some of the eccentricities of Oyamada’s style, such as the sudden switch, often mid sentence, from one character and location to another.

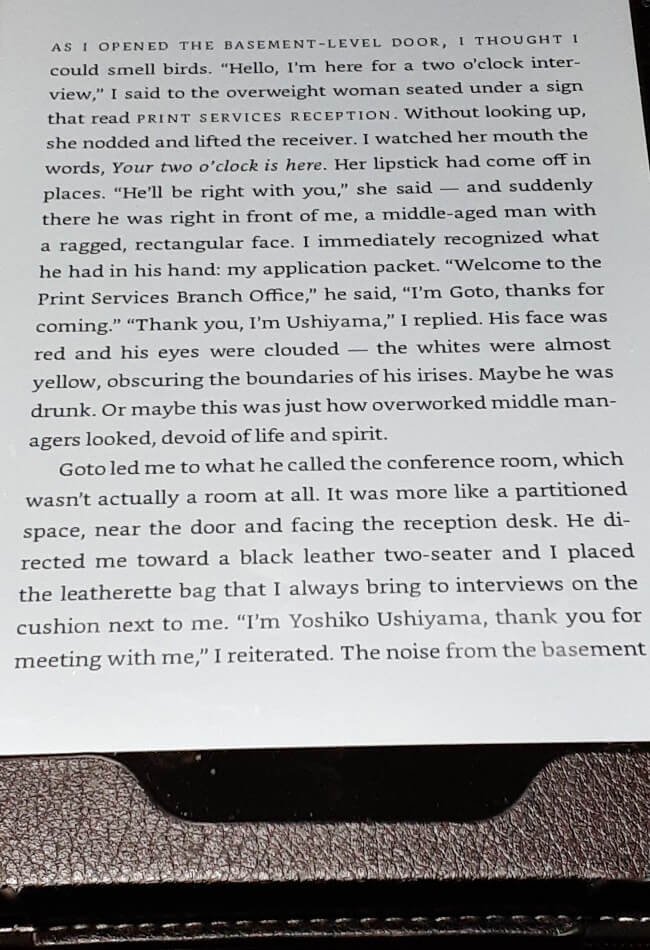

There is a moment in David Boyd’s translation of the opening that I deeply admire, which is how he renders the brief interaction between the receptionist and Ushiyama. (I take it that Ushiyama is a stand in for Oyamada, with a bit of word play thrown in for good measure.)

To understand how good at this sort of thing David Boyd is, I offer a fairly literal and bovine translation of the opening page of The Factory, followed by David Boyd’s version.

My Translation of the First Page of The Factory by Oyamada Hiroko

At the grey factory, when I opened the basement door there was the odour of birds.

On opening the basement door I was immediately confronted by a plump middle aged woman sitting beneath a sign that said “Printing Department Reception.”

“I have an appointment for an interview from 2 o’clock today but….”

Without looking at me she nodded, lifted the receiver and buzzed an internal line.

Her lipstick was blotchy and coming off in places.

No sooner had she said, “The manager’s coming…” than a middle aged man in a suit with a square-shaped reddish-brown face came in. It was clearly a pretty close internal call. In his hand were my CV and work experience form that I’d posted in advance, stuffed in an envelope with “CV enclosed” stamped on it.

“I’m Goto from the Printing Department. Thank you very much for coming today.”

“My name is Ushiyama. How do you do.”

There was no lustre in his face and his eyes were turbid, the whites were yellowish and the boundaries of his pupils had become vague. Was he drunk? Or was it the severe workload that the factory compelled middle managers…[to do that drained them of vitality and vigour and discoloured their faces?]

David Boyd’s Translation of the First Page of The Factory by Oyamada Hiroko

I watched her mouth the words, Your two o’clock is here.

The brilliance is in what is omitted and what is added. Compare the lumbering literalism of my translation to the economy and inventiveness of the professional’s. The parts of the original that he omitted I have placed in bold in my translation. The parts that he added I have placed in bold in his translation.

| My Translation | David Boyd’s Translation |

| Without looking at me she nodded, lifted the receiver and buzzed an internal line. | Without looking up she nodded and lifted the receiver. I watched her mouth the words, Your two o’click is here. |

| Her lipstick was blotchy and coming off in places. | Her lipstick had come off in places. |

| No sooner had she said, “The manager’s coming…” than a middle-aged man in a suit with a square-shaped reddish-brown face came in. It was clearly a pretty close internal call. In his hand were my CV and work experience form that I’d posted in advance, stuffed in an envelope with “CV enclosed” stamped on it. | “He’ll be right with you,” she said – and suddenly there he was right in front of me, a middle-aged man with a ragged, rectangular face. I immediately recognized what he had in his hand: my application packet. |

The brilliant part, for me, is the insertion of, “I watched her mouth the words, Your two o’clock is here.” Perfect! When I read it for the first time I liked it and assumed that it was a more or less direct translation of Oyamada Hiroko’s Japanese – and I found her all the more agreeable for such a perfect expression of the alienation or disconnectedness that the habitual round of factory and office work can induce. Ushiyama is reduced to a time-slot in somebody else’s schedule. The disconnectedness is ironically pointed up by the use of technology – an “internal line” – to act as a pretext for the receptionist to avoid anything but the most perfunctory communication with Ushiyama, and to call someone who is in the immediate vicinity.

Does Ushiyama Turn Into A Bird?

At the end of the novel, Ushiyama gives her colleagues a selective report of how she spent her half-day holiday the previous day. walking over a long bridge that connects the two halves of the factory complex and looking at the flocks of black birds. Then she pops upstairs to the toilet, but it’s being cleaned so she turns back and encounters a woman carrying a black bird up the stairs out of the basement. She stops to watch but the woman ignores her. She wants to ask a colleague about it when she returns to the office, but she was talking to someone, so she reluctantly gets on with her work. The novel concludes with her apparently turning into a black bird.

Here are the last few sentences of the novel with my translation compared to David Boyd’s:

| My Translation | Davd Boyd’s |

| I reluctantly grabbed a bundle of paper from my container and fed it into the shredder. For a while I absent-mindedly fed paper into the shredder. Then, in the instant when I took the last bundle of paper from the container by my feet and fed it into the shredder, I turned into a black bird. I could see people’s arms and legs. I could see grey crowds and I could also see green and smell the tide. | I turned back toward the morning container, grabbed a handful of pages and fed them into the shredder. I wasn’t thinking about anything at all, just feeding paper into the machine. Then, as soon as the shredder swallowed the last pages, I became a black bird. I could see people’s legs, their arms. I saw gray, a little green. I thought I could smell the ocean. |

The question that my student and I discussed was whether or not Ushiyama literally turns into a bird, or whether it is a flight of imagination disconnected from the seemingly meaningless repetitive work of shredding paper.

My student pointed out that the novel begins and ends in the basement of the printing department being associated with birds and an evocative smell. In the opening sentence, Ushiyama opens the basement door and is greeted by the smell of birds. In the concluding passage, it is in the basement of the printing department that she becomes a bird and smells the sea.

Our discussion took a theological turn as we talked about the potential for a declarative sentence to be read literally or metaphorically, as in the words of Christ, “this is my body…” What is the status of “is”? In Ushiyama’s sentence, “Watashi wa kuroi tori ni natte ita,” what is the status of “natte ita“? Should we be Roman or Genevan in how we read it? “Neither” is probably the most apt response; embrace, instead, the Japanese facility to engage with fantasy as if it were in the here and now without seeking to pin it down as this or that.

One thing we can note is that the factory is riddled with adaptive wildlife whether it be the black shags that live on the river banks, or the “washer lizards” that live in the washing machines in the laundry room, or indeed the varieties of green moss that grow in various parts of the factory. The workers too, seem to become little more than “adaptive wildlife,” and so we may presume that by the end of the novella Ushiyama has finally become one of them.

DH

David Boyd’s English translation of The Factory is available in on Amazon.com. The original Japanese edition is available on Amazon.co.jp. Search for: 小山田 浩子 工場