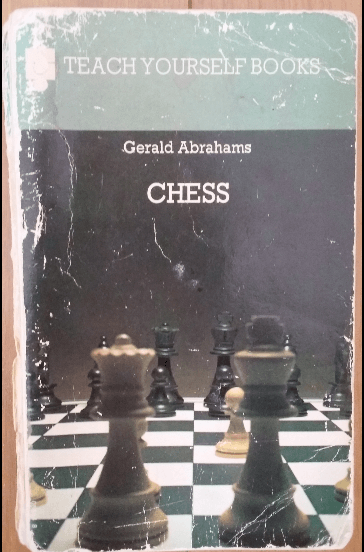

I bought my first chess book from the post office and general store in Sandhurst, Kent, England, some time around 1975 or 1976. The book in question was the paperback version of Teach Yourself Chess by Gerald Abrahams.

My original copy fell to pieces long ago. The one in the photo is a replacement edition I bought about ten years ago, which is now more or less on its last legs.

Teach Yourself Chess was first printed in 1948. Both my original and replacement copies were part of the third impression, printed in 1975.

Somerset, Summer 1976

I took the book on our family holiday to Somerset in the long dry summer of 1976, learnt the old descriptive notation and began to work through the book and play through some of the games, not too thoroughly, mind you, but spurred on by the promise that if “the reader,”

“…understands what he reads, then, as he works his way through the second chapter, he will find himself acquiring a certain capacity to think for himself about moves. After the second chapter he may even be thinking like a Chess player.”

ibid, p. v

The descriptive notation appealed to my feudal sensibilities; it seemed right and proper that each piece should be named according to its relation to the King or Queen, and each pawn should be named after it’s local lord, and even that the territory over which they passed should all revert back to the king or queen: “Pawn to King’s Knight Four” (P to KKt4), or “Queen’s Bishop’s Pawn x Knight” (QBP x Kt) and so on.

I didn’t know anything about Gerald Abrahams at that time, but his prose fired my imagination and revealed to me a marvellous world populated by players with exotic names such as Alekhine, Zukertort, the Duke of Brunswick and Nimzowitch, and the wonders of openings such as the Ruy Lopez and the Giocco Piano.

Another thing that attracted me was the erudition which Abrahams shared in an unspoken contract with the reader who was treated as an intelligent equal. Here was something to admire and aspire to.

The Preface to the first edition opens, for example, with this memorable observation:

“The philosopher Mendelssohn gave up Chess because he found it too serious to be a game and not serious enough to be an occupation.”

Teach Yourself Chess, p. v

I had probably heard of Mendelssohn the composer by then, but who on earth was this Mendelssohn the philosopher?

Two pages later, the Preface to the 1962 edition offered another mystery:

“… “time writes no wrinkles on Caïssa’s brow.” I think her smile that favoured Botwinnik in 1961 is the same that favoured him in 1948…””

ibid, p. vii

Clearly, Botwinnik is a chess player and a very great one too with a suitably exotic name. But Caïssa? A goddess presumably, though not one I’d heard of before.

The excitement and sense of wonder continued. The warlike nature of the game is emphasized in the opening chapter on the preliminaries of the game, as is its scientific nature, two things that appealed to my 13 year old self, aka, “the reader” who is happily considered capable of “adopting” a “standpoint”:

“Perhaps the best standpoint that the reader can adopt if he wishes to justify to himself the expenditure of time on Chess, is that he is studying a Science; not a Science as exact as Pure Mathematics, but a relatively unpredictable system of Dynamics analogous to the Dynamics of War.”

ibid, p.10

Yes!

Start With The Elementary Endgame In Mind

Once the preliminaries of the layout of the board, the moves of the pieces and the systems of notation have been dealt with, the book gets into the serious work, beginning with the end in mind, the elementary endgame.

Abrahams’ reasoning for starting at the end and conversely, leaving the openings until the end, is laid out in the Preface:

“Chess learning is only useful to those who can already play. That is why the proper place for a study of the openings is at the end of a Chess book, not at the beginning.”

ibid, p. vi

And so we come to Chapter Two, The Elementary Endgame, where the main course commences with a bang:

“In the language of the Persian poet, the purpose of the Chess player is to “mate and slay.”

ibid, p. 39

Who that seemingly renowned Persian poet may have been was an enigma to me, and yet one evocative of the grandeur of the game.

The Middle Game: Vision and Judgement

The second part of the book deals with the middle game, and is probably the toughest section of the book. The section on Mental Approach begins with an arresting claim that I suspect many chess players would question nowadays:

“When Edgar Alan Poe said that in Chess one calculated, he was demonstrating to Chess players his complete innocence of their mental processes.”

ibid, p. 97

What Abrahams means is that deduction, arithmetic and formulae are not very helpful to the ordinary player. He concedes that there are “negative” principles that experienced players use to regulate and discipline their play. However, players use what he calls,

“direct vision of move and counter move… that degree of vision which is imagination”

ibid p. 100

In addition to imagination, players use judgement based on their grasp of strategy when not trying to “see exhaustively,” (p. 100).

Yet, it is a mistake to regard those faculties of the mind as the workings of genius in the sense of a revelation of something mysterious:

“Meanwhile, let it be said that since the processes of Chess are always rational, always explicable, there is nothing, even in the cleverest moves, to make them the prerogative of genius. Or, to put it another way, genius in Chess is not a revelation of mysteries, but a degree of clarity: achieved, as the saying goes, by perspiration as well as inspiration. To regard Chess vision as the manifestation of an innate faculty is to make the error of confusing the simple with the easy, the logical with the innate. The mind does not work as directly as its mature capacities seem to indicate. To think that it does, whether in Chess or other processes, is to forget about the variety of forces that underlie the surface of the waterfall.”

p. 142

The Groundwork of the Openings

Part Three brings us at last to “the groundwork of the openings” and opens with an aphorism:

“The history of the development of Chess is the history of development in Chess.”

ibid, p. 178

It is one of those sentences that starts off with a promising ease and then brings you up sharp towards the end. What Abrahams means, it seems, is that opening theory in chess developed considerably over the previous century, and that development in chess is the key to the history of how chess developed.

What followed was my introduction to the wonderful world of chess opening names and theory. However, I don’t thing I absorbed much of it at the time, apart from the first few moves of the Ruy Lopez, and the Giucco Piano.

Back To The End Again

Having teased us at the beginning with the promise of the beginning of chess coming at the end, the chapter that follows the one on the openings is in fact a more detailed look at the endgame! As Abrahams puts it,

“We have seen that the endgame is the beginning of Chess. It is also the end – the latest stage and the most advanced.”

ibid, p. 218

The endgame chapter ends with an inspiring paragraph on the irrelevance of formal beauty in finding the best result in chess or science, and how something greater may be on offer:

“…the beauty of a piece of Chess is accidental, relatively to its effectiveness. Chess is a science and the good Chess move is the effective Chess move, as the good scientific process is the one that carries a result. The formal beauty of an idea is as irrelevant in Chess as, in Science, the aesthetic pleasure provided by colours that may occur in chemical experiments. Yet perhaps Chess gives something greater than the aesthetic. If the student of Chess comes to a stage where he can see a neat, elegant, or beautiful idea, and reject it because there is a better move available, then he has arrived at a high stage of Chess, and is approaching the attainment of that intellectual integrity which is the contribution of any science to culture.”

ibid, p. 234

The book concludes with a series of eighteen illustrative games which I remember struggling through on that distant summer holiday in Somerset, and am doing so again now, more than forty years later.

DH