This is a blog post about the novel Girl with a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier which I first published on a previous and now defunct blog. The review morphs into a discussion of Secret Knowledge by David Hockney. I read the novel and at least a part of Secret Knowledge back in 2002.

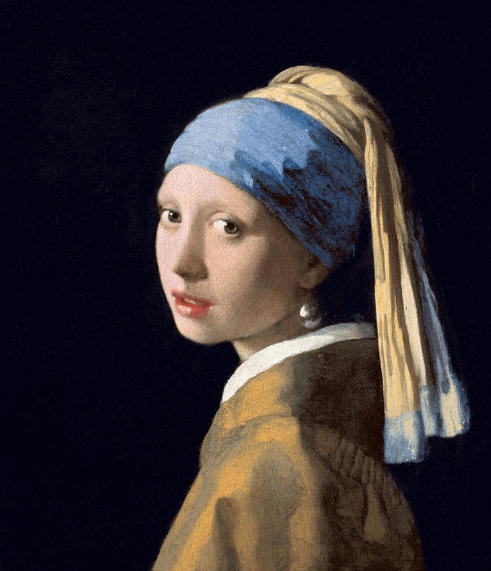

In 1665 Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer painted “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” a masterpiece which many consider to be “Holland’s Mona Lisa”.

An arrestingly beautiful girl with wide eyes turns her head to the viewer. Her lips are parted as if she is about to respond to somebody who has called her.

She wears an exotic head-dress unlike anything ever worn by the Dutch of the 17th century . The untucked cloth that hangs down from the top of her turban has not yet come to rest from the motion of the girl’s head as she looks around.

The dark background emphasizes the line of the girl’s face and gives her depth. The bright white collar of the girl’s ochre jacket contrasts with the dark background and compliments the whites of her eyes and the light that has caught her pearl earring.

Vermeer and 17th Century Holland

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) never left the small city of Delft, Holland, where he was born. At that time Delft was a thriving city, famous for its fine chinaware.

In the 17th century, after gaining independence from the Spanish, the nation of Holland was full of new wealth and confidence. The new ruling class of bourgeois Protestants had trading interests that spanned the globe.

During the reign of Britain’s “merry monarch”, Charles II (reigned 1660-1685), Dutch ships competed with British ships for command of the seas and oceans.

In 1667 the Dutch Fleet even sailed up the river Medway in Kent and attacked the navy dockyards at Chatham, destroyed and captured many British vessels and also threatened to sail up the Thames to London.

Vermeer relied on the new Protestant bourgeoisie for his living although he himself had converted to Catholicism and married a Catholic.

Proust on the View of Delft

“On his second voyage to the Netherlands in 1902, Proust first visited the town of Delft and then went on to The Hague. There, at the Mauritshuis, he saw Vermeer’s View of Delft. Years later… he claimed that it was at that moment he knew ‘I had seen the most beautiful painting in the world.'”

Eric Karpeles, Paintings in Proust, note, p. 340

The wives or daughters of his Protestant patrons can be seen in many of Vermeer’s paintings. They are engaged in common household actions such as writing a letter or playing an instrument.

Tracy Chevalier’s Novel, Girl with a Pearl Earring

In 1999 Tracy Chevalier’s novel Girl with a Pearl Earring was published to widespread acclaim. The novel, named after Vermeer’s famous painting, imaginatively recreates the life of its subject – the girl with the pearl earring – and her relationship with Vermeer and his household.

Girl With A Pearl Earring is the most beautifully written novel that I have read for some time. The prose is clean and lucid, rather like one of Vermeer’s paintings. It is the sort of novel that you do not want to put down once you have begun reading it.

How did Chevalier think of this idea for a novel? She explains:

“The idea for this novel came easily. I was lying in bed one morning, worrying about what I was going to write next. (Writers are always worrying about that.) A poster of the Vermeer painting Girl With a Pearl Earring hangs in my bedroom, as it has done since I was nineteen and first discovered the painting. I lay there idly contemplating the girl’s face, and thought suddenly, “I could write about her.” Within three days I had the whole story worked out. It was effortless; I could see it all in her face. Vermeer had done all my work for me.”

Tracy Chevalier, https://www.tchevalier.com/gwape/inspiration/index.html

Griet, the Protestant daughter of a Delft tile painter who lost his sight in a kiln accident, has to leave home and work as a maid to provide financial assistance for her family. She is taken on by Vermeer and his wife Catharina and goes to live and work at their house.

Griet has to try and maintain good relations with Catharina, with Catherina’s mother, Maria Thins, with the children of the house and the servants. This is not always easy to do as there are often jealousies and conflicting interests that threaten to compromise her.

Vermeer’s wife, Catharina, is too clumsy to be allowed into Vermeer’s studio. Unlike Griet, she lacks any feeling for art.

Vermeer notices Griet’s artistic sensitivity and quietly begins to train her as his studio assistant. Although it means Griet must now do a second job in addition to her duties as a maid, and although she must conceal her work from the rest of the household, she is happy to take on the responsibility because it allows her to develop her passion for colour and composition and also brings her into closer contact with the master of the house.

However, the tensions within the household come to a head when Vermeer’s most important patron takes an interest in Griet and requests that she be the subject of his next commissioned work…

Vermeer and the Camera Obscura

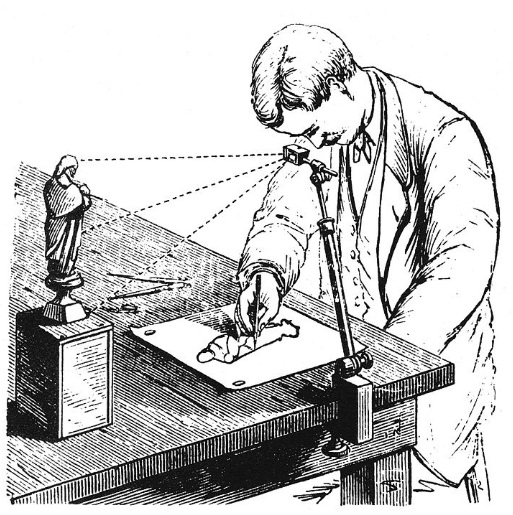

In order to write the novel Chevalier carefully researched Vermeer’s methods of painting, including his use of a camera obscura.

According to David Hockney, Vermeer was not the only artist to use such apparatus to assist him in his work…

…which brings me to another book that I am currently reading: David Hockey’s Secret Knowledge. [I wrote this in 2002, and I remember reading the book, but it seems that I never finished it, and it is no longer in my possession. Writing this in 2019 also gives me a sense of deja-vu; that I have written, or dreamed that I have written, before of a similar experience. DH Jan. 2019]

amzn_assoc_tracking_id = “clevercuckoon-20”; amzn_assoc_ad_mode = “manual”; amzn_assoc_ad_type = “smart”; amzn_assoc_marketplace = “amazon”; amzn_assoc_region = “US”; amzn_assoc_design = “enhanced_links”; amzn_assoc_asins = “0142005126”; amzn_assoc_placement = “adunit”; amzn_assoc_linkid = “cfb10bbf3b286d0c27c7244d80dbafe8”;In his book Secret Knowledge, Hockney discusses his theory that artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Velasquez, and Van Eyck created their masterpieces with the help of mirrors, camera obscuras and other optical devices.

This is not an entirely new observation as it has long been accepted that Canaletto and Vermeer both used a camera obscura.

However, Hockney believes that many more Old Masters, including Caravaggio, might have used such devices.

Did Ingres Use a Camera Lucida?

Looking at painting by Ingres, Hockney came to the conclusion that he must have used a camera lucida. Hockney then began to use one in his own work. As he looked at more and more paintings with his new hypothesis in mind he discovered what he believes to be a ‘photographic look’ dating back to 1430.

It is fascinating to trace the way in which the hypothesis directs his eye to notice things that have gone largely unremarked before, and yet, when brought to one’s attention, seem obvious.

For example, in Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (painted, 1596-8), Peter sits with arms outstretched, his right hand at the back of the picture away from the viewer, his left hand projecting out of the front right of the scene. Yet, his right hand is larger than his left hand – the opposite of what one would expect before checking the picture.

Hockney comments that features such as these

“…may be deliberate artistic decisions, or may be a consequence of movements of lens and canvas when refocusing because of depth-of-field problems.”

David Hockney, Secret Knowledge

Other examples include questions about the proportion of a subject’s head to the rest of her body. Where they differ it may indicate a movement of the camera lucida, a refocusing from one task – a swift deliniation of the head – to another – shifting the lens to capture the body and thereby altering the relation of the one to the other.

The confident fluidity of Ingres’ line in one place (nicely compared to that of a Warhole sketch traced from a projector), in contrast to his tentative “groping” for the line elsewhere suggests the use in one place of a camera lucida, and reliance on the naked eye in another.

The camera lucida would have been used to enable the artist to swiftly capture the outlines of whatever he was sketching, and the relation of one part to another. The camera lucida enables him to see both the subject and the paper he is drawing on at the same time, allowing him to draw with a swiftness and confidence unavailable to an artist who must rely solely on the naked eye.

In an age when artists worked to commission in workshops rather than the “studios” of the Romantics, celerity of execution was a vital consideration.

Why is there so little written evidence to prove this thesis? Secrets of the trade were kept close and passed down from master to apprentice within the privacy of the workshop.

Secret Knowledge is a compelling read, even if you remain sceptical. It is also beautifully illustrated and provides the reader-cum-viewer with much food for thought if one may move so gratuitously from reading to viewing to eating.

David Hurley

2002, revised and republished 2019