Over the last year or so I have created a Chess Opening Mnemonic Major Memory System For The 1.d4 Opening Repertoire for the White chess player. My memory system covers the first few moves (up to as many as 17 in one case) of 184 opening variations in the 1.d4 opening repertoire.

Here’s a video I made in which I attempt to explain how memory system works…

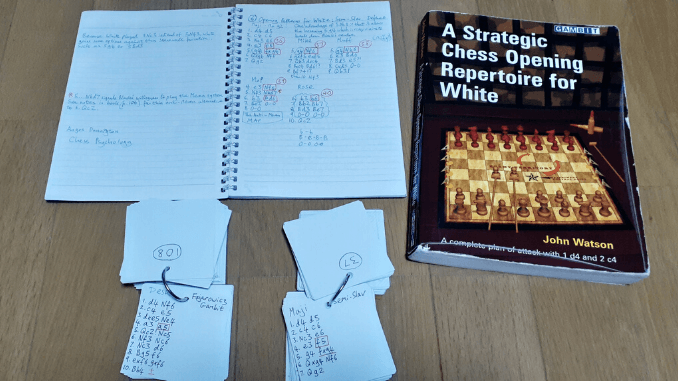

The project developed out of my attempt to improve my technique in the opening when I bought John Watson’s A Strategic Chess Opening Repertoire for White from Amazon.com just before heading to the U.K. for the British Chess Championships in Bournemouth in the summer of 2016.

The Slow Approach to Learning the Openings…

I spent the next couple of years slowly plodding through the book. I took copious notes of all the variations, with red lines linking the variations of variations and so on. Progress was slow. Painfully slow. In fact, by the summer of 2018 when I entered an afternoon open tournament at the British Chess Championships in Hull, I was bested by a teenager who responded to my 1.d4 opening with the Grünfeld Defence. (I posted a rather poor quality video about the game on YouTube.)

However, it was only when I got back to my hotel room and looked up the opening in Watson’s tome that I realized what it was. I had spent two years working through the book but had simply not absorbed the information well enough to recognise the Grünfeld Defence the first time I encountered it in a competition.

Let’s Try a Mnemonic Memory System…

So I decided to change my approach and create a truncated version of each of the variations and plug them into a mnemonic memory system to hammer them into my addled pate. I spent the next year or so mining the book and getting the first few moves of each of the variations into a notebook approximately in the same order as they appear in John Watson’s book.

Then, over the Christmas and New Year holidays I numbered all the variations, attached a keyword to each of them, and then copied all of the variations into two sets of study cards. The keywords are tied to the number of each variation by using a mnemonic memory system called the Major System.

184 Opening Variation Study Cards

I’m already feeling the benefit of having the 184 opening variations available in an easy-to-check format. So far I have learnt the keywords of the first variation of each of the different defences to 1.d4. I know, for example, that the 36th variation (the “Magi”) is the first of the five Semi-Slav variations that I have listed before the Nimzo-Indian kicks in with the 41st card (the “Rat”). However, the challenge for this year, 2020, is to take the next big step and create easy-to-remember stories that relate each opening variation to the keyword that is associated with it.

Once I have achieved that level of familiarity with the openings, I should be able to tell if my opponent is sticking to one of the plot-lines or is deviating from it or, as is more likely in the casual chess scene that I play in most of the time, has simply lost the plot. It should help me to get well set up in the opening and quite possibly to enter the middle game with a small but significant advantage, if I don’t screw things up on the way!

So, how does the mnemonic Major System work?

Introducing Dr. Bruno Furst

Before I answer that question, let me mention how I found out about it. Back in the late 1970s or early 1980s an American called Dr. Bruno Furst used to post ads in British newspapers with the headline, “You Can Remember.”

He was selling a memory course consisting of twelve lessons, a mnemonic dictionary and one or two other supporting materials. The sales copy was very well done and it sparked my curiosity, or whetted my appetite enough for me to buy the course and to work through several of the lessons. That’s how I learnt the Major System, although I don’t remember it being referred to by that name in the course itself.

The Major System

The system works by assigning a consonant to each of the ten digits of the decimal system, and then assigning a keyword to nine of those digits. (Zero does not need a keyword as it does not appear alone.)

- 1 =T = Tea (or D or Th sounds)

- 2 = N = Noah

- 3 = M = May

- 4 = R = Ray

- 5 = L = Law

- 6 = J = Jaw (or “-dge” or “Sh” sounds)

- 7 = K = Key (or hard “G” sounds)

- 8 = F = Fee (or V)

- 9 = P = Pea (or B)

- 0 = S

Vowels and other consonants do not stand for any number or digit. Instead, they are used to help create words. For example, I found it difficult to think of an easy-to-remember word for the 166th variation – T/D/Th + [J/-dge/Sh x 2], but with the help of a spare “w” I was able to come up with the word “dishwasher, discounting the “r” at the end as my repertoire has just 184 variations so clearly does not need to count the fourth digit.

Fixing the First Variation of Each Defensive System

Once I had all the keywords, and had created my 184 study card set, the first thing I wanted to remember was the sequence of defensive systems as they occur through the repertoire. Knowing where the first variation of each defensive system occurs will greatly assist me in finding my way around the rest of the repertoire. Here’s how it goes:

- 1 = Tea = Queen’s Gambit Declined

- 17 = Tack = Queen’s Gambit Accepted

- 22 = Nun = Slav Defence

- 30 = Mouse = Marshall Defence

- 36 = Magi = Semi Slav Defence

- 41 = Rat = Nimzo Indian Defence

- 51 = Lute = King’s Indian Defence

- 55 = Lily = Grünfeld Defence

- 61 = Jet = Benoni systems

- 86 = Fish = Dutch Defence

- 100 = Theseus = Budapest Defence

- 107 = Desk = Fajarowicz Gambit

- 119 = Hot-tub = …d6 + …g6 Systems

- 122 = Don Juan = …d6 + …Nf6 Systems (added to this list in 2021)

- 129 = Watanabe = Old Indian Defence

- 130 = Thames = Modern Defence

- 140 = Trees = English Defence

- 149 = Turbot = Bogo Indian/English Hybrid

- 154 = Hitler = 1..Nf6 2…b6 Systems

- 160 = Duchess = Black Knights Tango

- 166 = Twitchy Witch= 1…Nc6

- 171 = St. George Defence

- 174 = Digger = 1…b5 2…Bb7?!

- 175 = Tickle = 1…Nf6 2…a6

- 177 = Teacake = The Englund Gambit

This sequence is probably best recalled by placing each word in a memory palace. It also helps to notice sequential patterns such as the 2,1,2,1,2,1 pattern of inital letters that runs from Tea and Tack through to Jet: T, T, N, M, M, R, L, L, J.

#36 The Magi – Or How The Star Leads Me To The 4…f5 Variation of the Semi-Slav

In the video I demonstrate how the keyword serves not only to locate a variation in the sequence, but also to trigger a story that is tied to the actual sequence of moves in the specific variation. As we are in the middle of the Ephiphany season I use the 36th variation (the “Magi”) as an example. It is the first of a series of Semi-Slav variations and goes like this:

So here is the story of the Magi told in such a way that it will help me to remember the move order of the 36th variation in my sequence.

1. d4 d5

2. c4 c6

3. Nc3 e6

4. e3 f5

5. g4 fxg4

6. Qxg4

6. … Nf6

7. Qg2

The standard 1.d4 opening…

3…e6 takes us into the Semi-Slav.

4. e3 = the 3rd of the 3 Wise Men (the d4, c4 & e3 pawns). The star appears as an f5 comet, which gives off some light at g4, goes dark again and then…

it illumines the sky as the Queen of Heaven. It is so bright that the dark knight, Herod comes out to have a look.

The star descends right over the stable where the g1 horse is by the manger.

On the Role of Memory Systems in Chess

There are plenty of chess players and experts out there who will tell you that you should not focus on remembering opening sequences. It is certainly the case that you need to spend a lot of your study time developing your technique in the middle and endgame.

The only thing is, many of the experts who depreciate the role of memory systems already have a large repertoire of variations stored up in their memories through the experience of playing and studying the game intensively over many years.

For amateur and casual players such as myself (aka the #PubChessBluffer ), devoting a bit of time to creating some kind of repertoire memory system as I am attempting to do here with White (and later this year with Black as well), seems to me to be a useful way to make swifter progress and to eliminate early losses due to naive set up mistakes.

Of course, we should also be studying the other stuff, and part of my study syllabus is to move on at some stage to a closer study of Jeremy Silman’s books, How to Reassess Your Chess, The Amateur Mind and Silman’s Complete Endgame Course.

In the meantime, I’m having a blast trying to exercise my memory by dusting off methods I first studied several decades ago thanks to the methods I learned by studying Dr. Bruno Furst’s course, You Can Remember!